The world’s power grids need a lot of money – and a lot of new mileage – to be on track for net zero. Annual grid investment reaches $811 billion by 2030 in BloombergNEF’s Net Zero Scenario, driven by rapid growth rates in clean power, electric vehicles, and other low-carbon technologies. That’s nearly three times as much as the flowed into the sector last year.

Even in a slower, economics-led transition, grid spending stays elevated compared with past levels. BNEF’s Economic Transition Scenario sees annual grid investment hit $483 billion by 2030, 58% above the average investment seen in the first four years of this decade.

Wires, cables and towers

Renewable energy projects in remote locations – think solar power plants in the desert, or wind turbines in the middle of the sea – need hundreds of kilometers of new transmission lines to carry power from where it is generated to where it is consumed. The Net Zero Scenario’s transmission grid doubles in length between now and mid-century, by which time three-quarters of power come from wind and solar.

The distribution grid – the lower-voltage network that typically brings power to consumers – grows less dramatically in length, but new cables and wires are still needed. Aging grids, especially on the distribution side, are being strategically replaced with lines that can carry more power. Demand-side flexibility and small-scale batteries reduce the need for distribution grid buildout but come with a price tag.

Digital tools and flexible demand

At the same time, digital investment is playing a critical role in grid buildout. Historically, power flowed mainly in one direction, with generation injected into the transmission grid and then distributed via distribution wires. Now that rooftop solar panels are pushing electricity into the grid, these flows are getting more complex, and digital technologies are helping balance and maintain grids – and keep them safe.

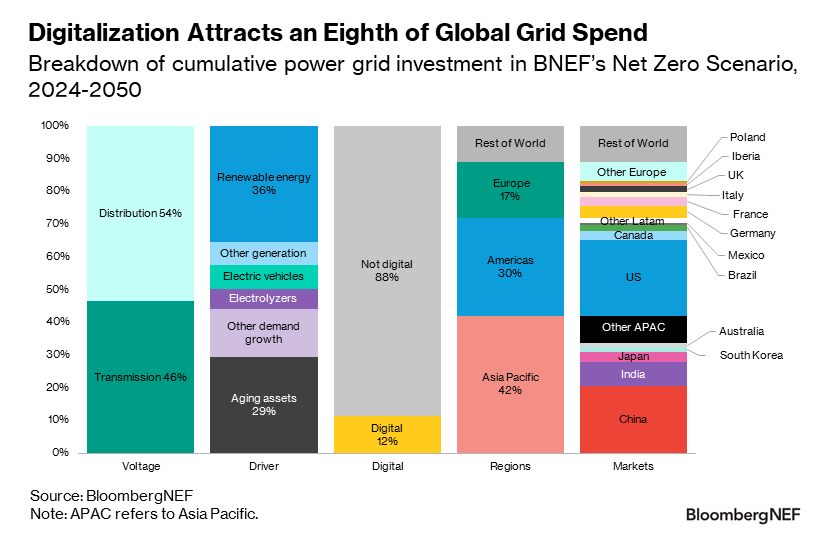

On average, 12% of 2024-2050 grid capital expenditure (capex) goes into digital technologies – although total spend is much higher, as most software charges appear on operational expenditure (opex) spreadsheets. As advanced analytics of grid data moves into the cloud, utilities are shifting their digital spend from in-house capital investment to operational charges. This poses a regulatory challenge: in most of the world, grid companies earn returns as a set percent on their capital investment, which means that moving spend from capex to opex requires a new type of earnings regime.

Power grids do not see a constant rate of demand. Just like highways are built to accommodate morning and evening rush hours but remain quieter in the hours in between, power grids are sized to accommodate the heaviest hour of electricity use, which leaves them under-utilized at other times of day or during different seasons. A rise in variable renewable energy and demand that flexibly follows renewable generation patterns can lead to a change in grid utilization. This, too, warrants spend on digital technologies to control demand, reduce curtailment and improve grid utilization.

Rising investment could trickle down to consumer bills

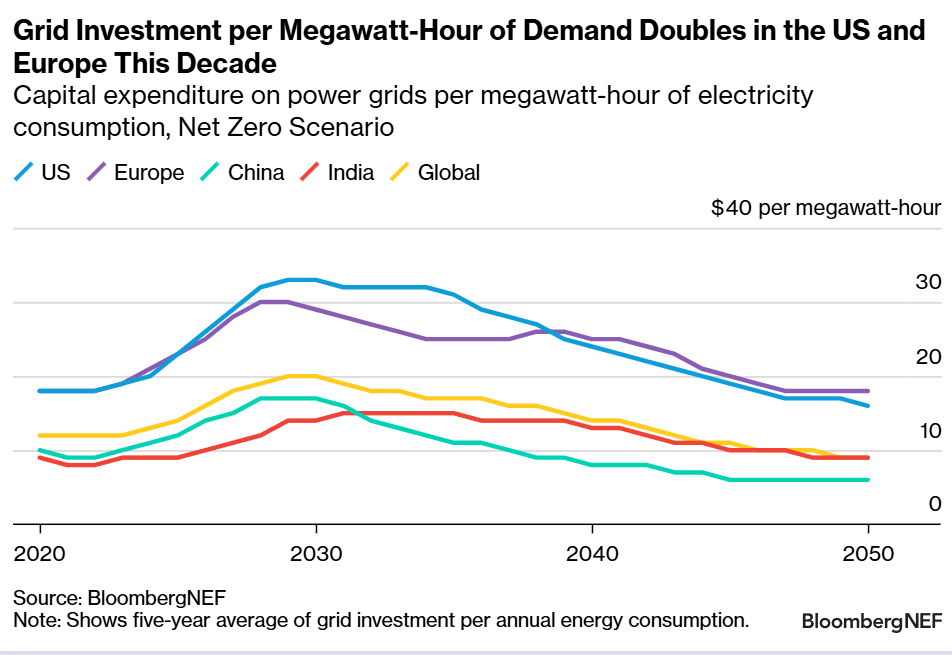

New grid investment, whether digital or traditional, is recouped through grid charges on the bills of all energy consumers – and in some cases generators, too. If grid investment grows at the same pace as demand, these rates stay more or less constant. However, if grid investment is driven by something other than rising demand – such as aging infrastructure needing replacements or renewable energy connecting from remote locations – the cost per megawatt-hour of energy can increase.

The grid investment cost per megawatt-hour nearly doubles over 2020 to 2030 in both Europe and the US in BNEF’s Net Zero scenario. Fortunately, this does not directly translate into doubled consumer bills as this representation is simplified: in reality, most grid companies around the world depreciate their investments over 30-45 years, which spreads out the cost of investment.

Grid charges also cover other costs, like maintenance and operational expenses. And the rise of renewable energy, which has no fuel costs, can lower the energy part of consumer bills. Consequently, the balance between different energy bill components is likely to change, but that need not lead to a significant increase in the price tag for consumers.

BNEF clients can access the full report here.