Global oil markets are standing on the brink of a profound restructuring. After months of talk, Europe’s boycott of all Russian seaborne crude oil kicks in on December 5, accompanied by the G7’s price cap of $60 per barrel on Russian oil. With Russian oil accounting for 10% of Europe’s total imports – to the tune of some 1.2 million barrels per day (b/d) – the boycott will pack a punch. The question is for whom. Amid a dearth of alternatives, much suggests that Europe will take more of a hit than Russia.

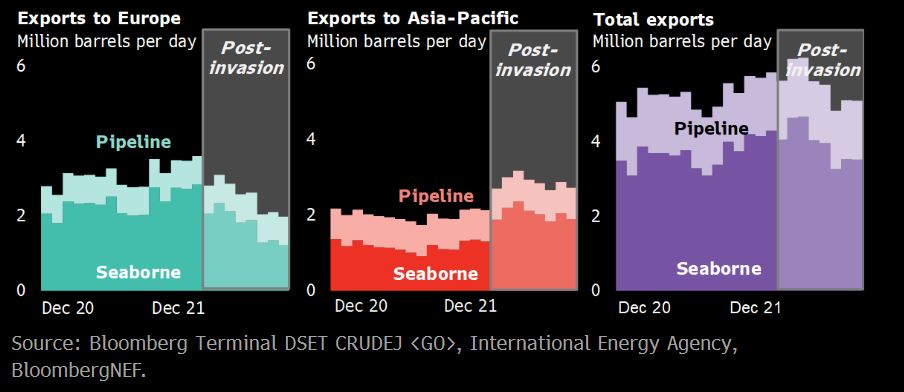

- Europe’s maritime imports of Russian crude have dropped by about 1 million b/d compared to 2021, but remain extensive. The region also continues to receive 0.8 million b/d of pipeline crude – exempted from sanctions – and a similar amount in the form of oil products, pending a ban from February 2023. Russia could prematurely wind down those supplies to Europe in retaliation, with higher prices compensating for export losses.

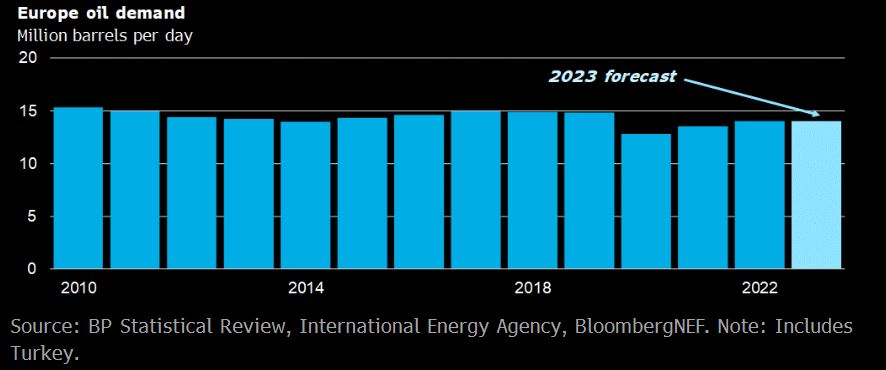

- Oil demand in Europe remains robust. Demand in 2023 is set to come close to pre-pandemic levels, as gas prices encourage gas-to-oil switching and aviation and road activity boom.

- Alternatives to Russian oil are scarce. Global oil supply investments in 2022 fall $170 billion short of what is needed to meet projected demand growth, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Many of the world’s largest producers are also embroiled in political instability or face dwindling reserves.

- Surging transport costs could inhibit the extensive restructuring of shipping routes that the oil ban might entail. Meanwhile, sanctions could herald an emerging dynamic in which Russian oil gets to Europe via adjacent roundabouts to mask its real country of origin.

The boycott begins

Europe has been increasingly shunning Russian energy since the invasion of Ukraine in February, and the new boycott of Russian seaborne crude – designed to deal a deadly blow to Russia’s energy sector – is the most powerful item yet in the EU’s toolkit of retaliatory measures.

The impact of this boycott is hard to overstate. Europe remains heavily dependent on Russian oil, and the amount it seeks to cut off is sizable. As recently as October 2022, Europe still imported some 1.23 million b/d of Russian seaborne crude oil – about 10% of its total oil demand. Pipeline and oil-product transport – which we will not address here, as they are (so far) unaffected by the boycott – add another 1.5 million b/d or so to the mix.

About 0.35 million of these 1.23 million b/d are exported via Russia’s Novorossiysk port on the Black Sea. Most of this oil comes from Kazakhstan. While exempted from the boycott, these volumes remain subject to supply interruptions as they cross Russian territory and utilize its export facilities.

So far, Europe’s attempts to ostracize Russian fuels have not yielded any substantive results. Russia’s oil exports remain around the 2021 average, since China and India absorbed most volumes that Europe shed.

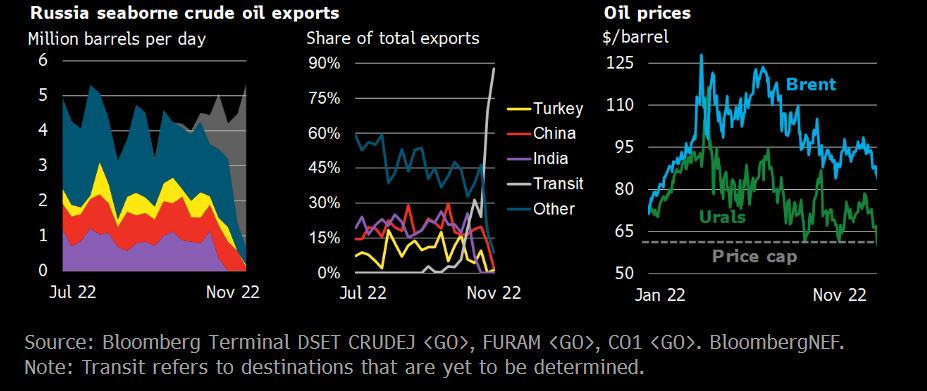

However, China’s oil demand has lagged expected growth as Covid-19 continues to beset the country. There are also limits to how much India is willing to take from Russia. Ships from Russia take several times longer to reach India than those departing from India’s usual suppliers in the Persian Gulf. Free shipping capacity meanwhile is scarce. While freight costs have fallen in recent weeks, crude oil shipments from the Black Sea to Singapore – used as a proxy for Russian oil shipments to Asia at large – were about 66% higher in October 2022 compared to February 2022. As India ups its imports from Russia, shrinking availability of tankers could further push up transport costs, eventually making discounted Russian crude less appealing than the Middle Eastern alternatives.

Rerouting the 1.2 million b/d cut off from the European market will not be an easy task for Russia – nor will it leave the global oil market unscathed. While the sanctions are intended to curtail the cash flow of Russian energy, their real impact remains to be seen. Potential consequences could include higher transport costs for the global oil market across the board, or higher crude prices as supply falls short.

Short-term, the price cap may be irrelevant

The EU embargo is accompanied by an oil price cap prohibiting non-EU countries from purchasing Russian crude for more than $60/barrel. Upon non-compliance, states will be barred from using shipping services and insurance from EU and UK providers – which dominate both markets – for 90 days. The cap only impacts shipments loaded from the December 5 onward, with shipments that have already been signed for remaining unaffected.

Russian officials reiterated that the country will not sell oil to states adhering to the price cap. Speculation has consequently been rife on how this will affect Russian oil exports and to what extent other nations would comply with it. India announced that it will continue buying Russian crude and that it will be unaffected by the price cap as it plans to use non-Western shipping services. The situation is less clear for both China and Turkey – the only other large non-Western offtakers – which have not articulated any explicit stance.

China’s independent refineries, accounting for some 25% of the country’s refining capacity, are among the major buyers that have already ordered Russian crude cargoes for the upcoming two months at a steep discount. Urals prices – the benchmark for most Russian crude sales – have been falling as the day of the boycott approached, now hovering around $65/barrel.

Further downward pressure amid the high uncertainty surrounding Russian crude seems likely, potentially rendering the price cap practically irrelevant in the short term. By contrast, the price trajectory of other benchmarks might find itself back on an upward trend as the market runs the risk of falling short by around 1 million b/d. As the gap between Urals and other crudes widens, the incentive for China and India to buy Russian oil grows.

The key question then becomes whether those countries will rely on shipping providers and insurers outside the scope of the Western world to sustain their supply chains. Doing so would allow Russia to save face, as the country would live up to its promise to not deliver oil to nations abiding by the price cap. While Russia has been expanding its fleet over the past months, analysts, traders and officials still believe that the country would lose some 1 million b/d in exports if it relies solely on its own tankers.

That said, the world’s so-called shadow fleet – ships operating outside of the fringes of jurisdictions and monitoring systems – has had plenty of practice with Iran under sanctions. The past months have given them additional preparation time. It stands to reason that much of those 1 million b/d will find their way into Chinese and Indian harbors without any backup from Western tankers, banks or insurers.

Oil demand is here to stay – at least in 2023

As of late 2022, oil demand worldwide stands at about 99 million b/d – roughly the same level as in 2019. The Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS) of the International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that oil demand will grow to about 106 million b/d by the early 2030s before beginning a slow decline. BloombergNEF anticipates that oil demand will peak earlier, in 2030, in our Economic Transition Scenario.

Yet while the ‘when’ and ‘how high’ of the oil-demand peak can be contested, it is extremely improbable that we will reach peak oil demand before 2025. Economic recessions afflicting the global economy and China’s struggles to emerge from lockdowns may both dampen oil demand growth, but neither are likely to cause it to decline. The argument that higher oil prices will expedite the energy transition is also trivial in the short term, as any large-scale solution will be neither commercially available nor deployed within a year or two. Crashing the economy by disrupting its energy supply is certainly possible, although any democratic government facing (re)elections is going to be rather reluctant to let that happen.

An oil deficiency looms

More importantly in the short term, there is not enough oil in the market to meet growing demand, and many indicators point toward a continued shortfall. The 2022 investment in oil production is forecast to fall $170 billion short of the $470 billion needed annually to meet expected demand growth, according to the IEA’s STEPS. Even the more bearish demand outlook of the Announced Policies Scenario (APS) calculates that total upstream oil investments are $80 billion below what is needed. The track record of the past years looks equally sobering: investments that dropped post-2014 have yet to recover, as producers remain conservative in their spending.

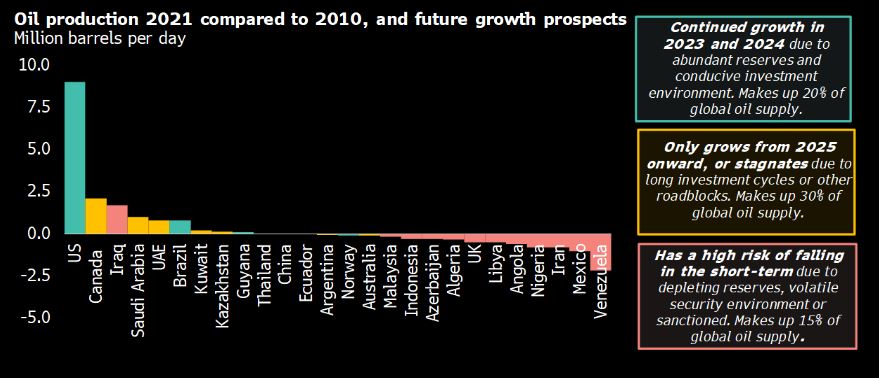

Investment cycles for upstream projects typically span some four to seven years before first oil is produced. We are thus likely entering a phase where the investment drought is starting to take effect. A closer look at individual producers reaffirms that supply is tight. More than half of the largest oil producers globally have lost production capacity over the past decade.

For many of those countries, such as Angola, Azerbaijan, Indonesia and the UK, this is mainly the result of dwindling reserves. Political instability and a resulting recent exodus of oil majors limits upside in Iraq and Nigeria. Libya’s situation remains equally volatile, while Mexico’s investment environment has been closed off to international oil companies and its national oil company is the most indebted of its kind in the world.

These structural factors won’t disappear overnight. Even well-positioned producers such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are not poised to increase their output notably before 2025. The upcoming year will see added production of only 2 million b/d, of which half will be added in the US and the remainder will be distributed between Brazil, Guyana and Norway. (For more on the production outlook of 16 of the largest oil-producing countries in the world, see BNEF’s National Oil Companies’ Oil and Gas Business Analysis.)

Moreover, these estimated additional 2 million b/d are unlikely to reach the market before the end of 2023. If the 1.2 million b/d from Russia that Europe has now boycotted were to disappear from the global stage, it would leave a yawning gap that at best could be filled by further draining the OECD’s strategic petroleum reserves. Yet those reserves have already dropped from about 4.4 billion barrels in 2019 to less than 4 billion barrels in the second half of 2022. An intensified reliance on reserves could leave the market vulnerable to further or prolonged price shocks.

The same demand and supply mechanics are unfolding for Europe

Rampant headline noise might give the impression that Europe’s oil demand is already in a free fall amid surging fuel prices. Yet the 2022 IEA estimate for Europe’s oil demand is set to be about 500,000 b/d higher than for 2021. A combination of rebounding aviation activities, high traffic levels during the holiday season and some gas-to-oil switching amid skyrocketing gas prices has underpinned this growth. European oil demand for 2023 is likely to hover around the current year’s level.

Europe’s oil demand over the past ten years has remained extremely robust. Even as commuting, aviation and swaths of industrial activities ground to a halt in 2020, overall demand dropped by just 2 million b/d, or about 15%. Absent a disruption to society at large akin to that of Covid-19 in scale, Europe will have to replace its Russian imports.

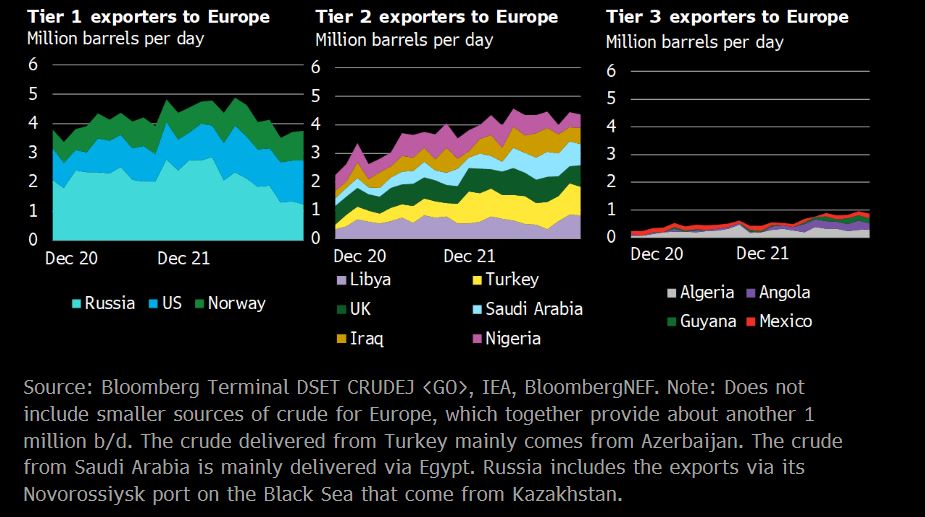

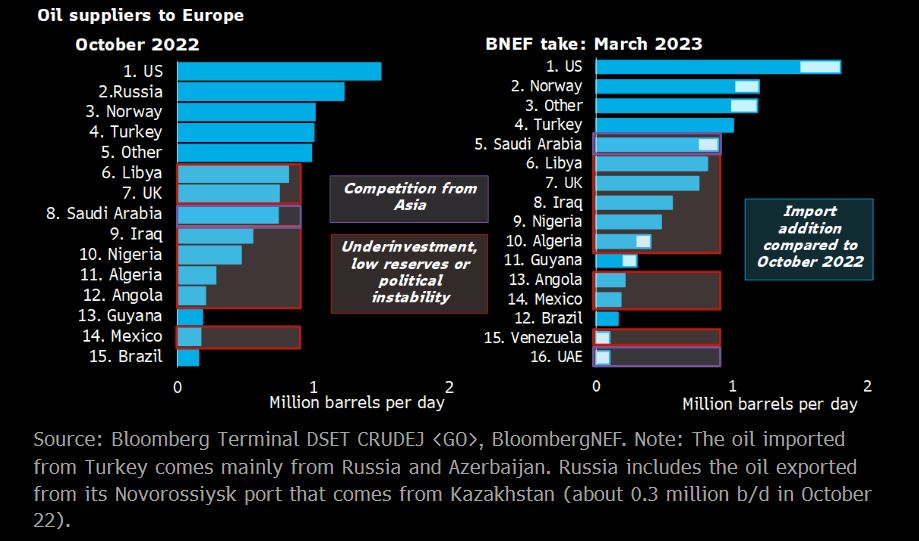

The region’s import slate has changed relatively little over the past two years. As of October 2022, Russia remains Europe’s second-largest source of seaborne crudes, despite dropping by more than 1 million b/d (to 1.23 million b/d) between March and October. Some of the volumes have been replaced by Saudi Arabia (+0.5 million b/d) and the US (+0.4 million b/d). Turkey is also sending an additional 0.5 million b/d to Europe, although this oil comes largely from Azerbaijan and Russia. All three countries would need to send more to Europe to fully replace Russian supply.

Turkey’s import of Russian crude has risen notably over the past year. This could herald an emerging dynamic in which Russian crudes get to Europe via adjacent roundabouts to mask their real country of origin. Furthermore, as large refining centers like India accelerate Russian crude oil imports, oil product flows – like diesel – are increasing to Europe, meaning the European market is still guzzling up oil of Russian origin.

Few other major oil producers that sell to Europe have the spare capacity necessary to turn up their output at will, and their exports to the European market have increased little (if at all) over the past year. Long-term contracts – which are particularly prevalent in the Gulf States of the Middle East – further limit flexibility.

Where will Europe get its oil in 2023?

It is hard to see how Europe will replace its 1.23 million b/d of Russian crude in the short run. BloombergNEF has mapped out four scenarios that might unfold for Europe’s major (potential) suppliers:

-

Norway and the US

have the most leeway and are arguably most inclined to fill the gap left by Russian oil. Both countries number among the few worldwide that are expanding oil production, adding some 0.2 million b/d and 1.0 million b/d respectively over the next year. As shipping costs climb, Norway might see its Asia-oriented exports diverted to Europe. On the other hand, the very light quality of US tight oil could be problematic for European refineries that are attuned to Russia’s medium-heavy crude, complicating a like-for-like substitution. Altogether, Norway and the US might be able to provide some 0.5-1.0 million b/d to Europe by mid-2023. It is difficult to see how such a number could be reached any earlier.

- The

Latin-American producers

are likely to step up their game. Rumors have been emerging of negotiations with Venezuela to allow the heavily sanctioned country to export some oil to Europe. The country has lost more than 2 million b/d of production since 2017 amid crippling sanctions – production that could potentially be restored if they were lifted. Yet Venezuelan crude is very heavy, which would make it difficult and costly for European refiners to process. High transport costs represent another hurdle, as do the years of mismanagement and underinvestment that still plague the country’s oil sector. By contrast, Guyana – which is slated to add at least 300,000 b/d in 2023 – has lighter oil that Europe’s refineries could handle well. Brazil might also provide some relief.

-

Middle Eastern Gulf producers

– notably Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – will add some 200,000 b/d to Europe’s import basket. Long-term contracts with Asia-Pacific consumers and limited spare capacity make any further uptick unlikely in the months ahead. That said, both countries consume large amounts of oil for their own power generation. Both might step up purchases of discounted Russian crudes to meet this demand, allowing them to divert more oil to exports. Additionally, much will hinge on whether China and India will opt to further raise their purchases of Russian crudes, which could free up exports from the Gulf producers to send to Europe.

- The

other Middle Eastern and African producers

remain in a precarious position. Algeria needs to meet burgeoning domestic demand from its growing population while also facing dwindling reserves. Libya is stricken by political unrest. Iraq and Nigeria have been abandoned by oil majors such as Shell and ExxonMobil over the past years amid security concerns and divestment drives. Angola’s reserves are also being depleted. Altogether, an uptick of several hundred thousand barrels might be possible, but those would have to be diverted from Asia-oriented exports and would be highly volatile

.

The BNEF take

As the price of Russian oil hovers around the price of the G7 cap, the short-term impact of the sanctions on Russia will likely be limited. On the flip side, an oil supply shortage for Europe seems imminent.

In the near future, the continued substitution of Russian oil for Middle Eastern crudes in China and India and a restoration of Venezuelan exports seem to offer the greatest opportunities for mitigating impacts on Europe. Yet heightened Russia-Asia trade would require significantly more shipping capacity, as the volumes intended for the European market are shipped mainly from Russia’s Baltic and Black Sea ports. Any discount to the purchased crude will be counteracted – at least somewhat — by heightened freight costs. Long-term contracts between Asia and Middle East suppliers provide another ceiling to rerouting.

Getting Venezuela back on board is also easier said than done, with the country’s government potentially realizing the precarious situation of the OECD countries and using it to its advantage by adamantly refusing any deal that seems reasonable to Europe and the US.

The only true panacea seems to be demand destruction. In turn, this would require heavy disruptions of societal activities, not unlike those seen during Covid-19. With many European countries holding elections in the years ahead, such measures are unlikely to be a preferred choice among incumbent governments.