By Kamala Schelling, PhD, Editor, BloombergNEF

Wheat is in the headlines as Russia’s war in Ukraine again upends supply lines, convulses prices and threatens to leave more people hungry. Yet geopolitics aren’t the only reason to worry about the world’s harvest.

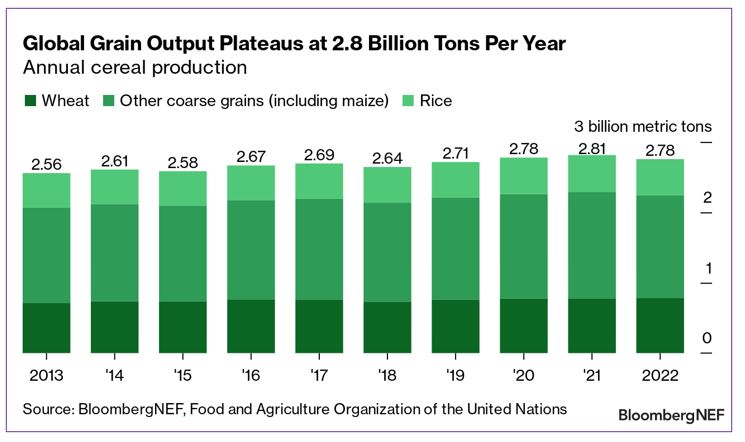

Of the nearly 3 billion tons of grains produced in 2020, the vast majority – equivalent to 60% of the world’s calories – came from annual varieties. These crops must be planted anew each year, though, resulting in soil degradation, loss of biodiversity, and the release of carbon into the atmosphere.

Perennial grains could be sustainable agriculture’s silver bullet, potentially doubling farmer profits and increasing nutrient uptake by half. And companies from General Mills to Patagonia are starting to take notice.

Grain production has grown alongside global population. In 1980 (population 4.5 billion), the world produced 1.2 billion metric tons of grain, including wheat, rice, and maize. By 2020 (population 7.8 billion), yields had grown to 2.8 billion tons.

But that rate of growth can’t continue forever. Land is limited. Climate change, farm degradation, and the costs of pesticides and fertilizers have destabilized global supplies. World cereal production is forecast to decline 0.6% this year, thanks to adverse weather conditions and a 40% drop in Ukrainian wheat planting as a result of the war.

“Agricultural intensification, land-use change, and the cultivation of annual crops have turned 1.3 billion hectares into marginal land,” says Caroline Lewis, a sustainable agriculture analyst at BloombergNEF. “That’s an area roughly the size of Antarctica.”

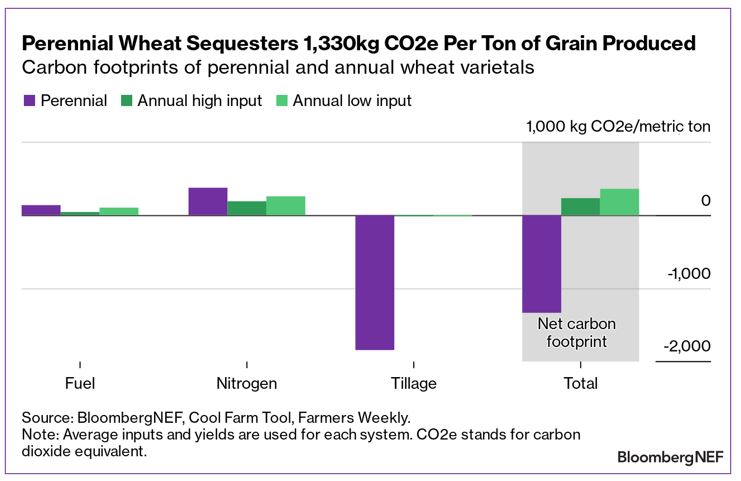

Enter perennials. “Perennial varietals are remarkable,” says Lewis. “Some benefits are obvious. By eliminating the need for seasonal tilling, perennials save farmers money on fuel and minimize emissions from tilling equipment and soils. Other benefits are more subtle. For instance, perennials develop more extensive root systems, which help sequester carbon in the soil.”

But there’s a catch. Or several. Cultivating perennials has some major challenges.

Initial seed costs may be high, perennials tend to mature later in the season, and large agribusinesses have so far shown a notable lack of interest in grains that as yet don’t match the yields typical of annual varieties.

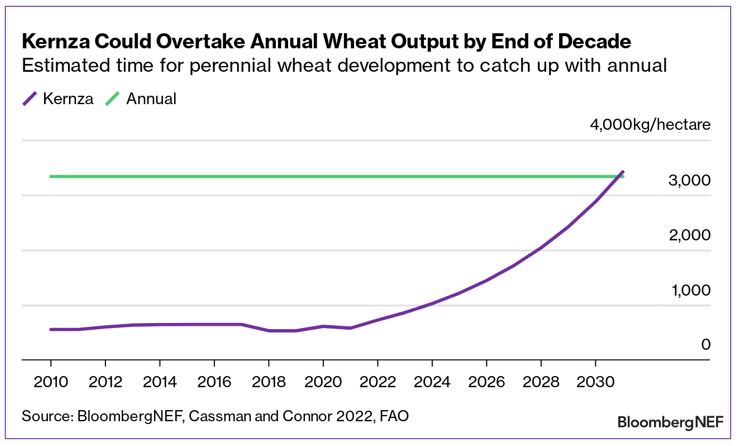

So far only one strain of perennial wheat is commercially available — trademarked as Kernza. Still, it is fielding commercial interest from companies that want to make sustainability claims and offset their Scope 3 emissions.

Patagonia – a B Corporation and ‘1% for the Planet’ certified company – is offering Kernza fusilli pasta. Perennial Pantry is selling Kernza flour, crackers and wholegrain products. Cascadian Farm, which is part of General Mills, has produced Honest Toasted Kernza Cereal. And the varietal is making its way into adult beverages: a Kernza Pils from Patagonia Provisions and Dogfish Head is available in 15 states in the US, and a handful of small distilleries have released Kernza whiskeys.

Kernza is picking up steam, and its yield per hectare could surpass that of annual wheat by around 2030.

There are a variety of pathways — both natural and policy-based — to encourage perennial wheat adoption. “Growing a diverse mix of perennials has been found to regenerate soils, suppress pests, and provide forage for livestock,” says Lewis.

“But if that in itself isn’t enough, a specific market or accreditation scheme that recognizes perennials’ environmental benefits could facilitate their adoption. The inclusion of perennial crops in agricultural insurance programs could help, too.”