With around three weeks to go until the start of the COP27 summit in Sharm el-Sheik, Egypt, the need to urgently address the climate crisis has never been clearer. Pakistan and Nigeria have experienced devastating flooding this year, Europe sweltered in a record heatwave over the summer, and Kenya and Somalia have been ravaged by a catastrophic drought.

Yet, at a time when unified global action is required, November’s climate talks are at risk of being overshadowed by other world events – namely, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, frostier relations between the US and China, energy and food crises, and inflationary pressures.

Wael Aboulmagd, Egypt’s special representative for COP27, urged countries last month “not to use this unfolding geopolitical situation as a pretext for backsliding.” The host nation is aiming for this year’s conference to focus on the implementation of pledges, with support for climate adaptation, making promised finance flows a reality, and compensation for loss and damage in the spotlight.

The COP summits are an imperfect process at the best of times, although the meeting in Glasgow last year did make progress, with bolder commitments on limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius and a deal reached on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, paving the way for a global carbon market. As COP27 looks to build on the momentum of its predecessor, here are three charts from BloombergNEF on what to watch out for.

1. Greater ambition and following through on pledges are essential

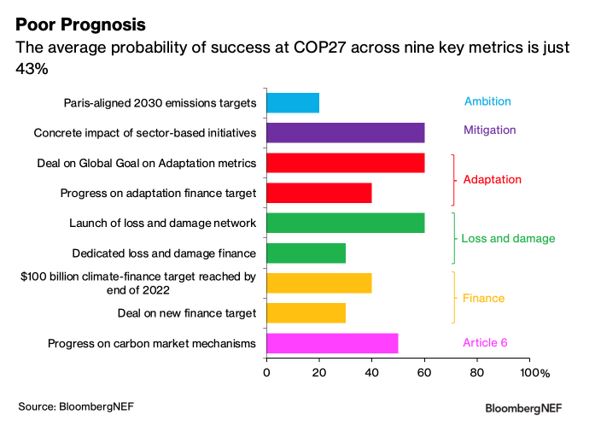

As the November 6 start date rapidly approaches, BNEF estimates COP27 has a less than 50% chance of being a success – or just 43% to be more precise. This assessment is based on the nine most important areas where progress needs to be made, such as the ambition of parties’ 2030 emissions targets and movement towards the goal of doubling finance for climate change adaptation from 2019-2025.

The likelihood of the ambition of emissions targets being sufficiently raised to meet the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement stands at just 20% in BNEF’s estimation – the lowest of the nine metrics. Even if all G-20 nations hit the 2030 goals laid out in their Nationally Determined Contributions, only three – the US, UK and Australia – would lower emissions by the levels required to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century.

The poor overall outlook is partly down to the harder task that this year’s summit faces versus COP26 in getting governments to actually follow through on the promises they have made.

“Last year’s COP was very much about good intentions – 1.5 degrees Celsius, no more coal, zero-emission vehicles, et cetera. But this year’s COP will be about how to deliver on those good intentions,” says Victoria Cuming, head of global policy at BNEF.

2. A path to the elusive $100 billion must be pinned down

One of Egypt’s criteria for a successful COP is to ensure that “no country or group is left behind”, and climate finance will be key to ensuring a just energy transition.

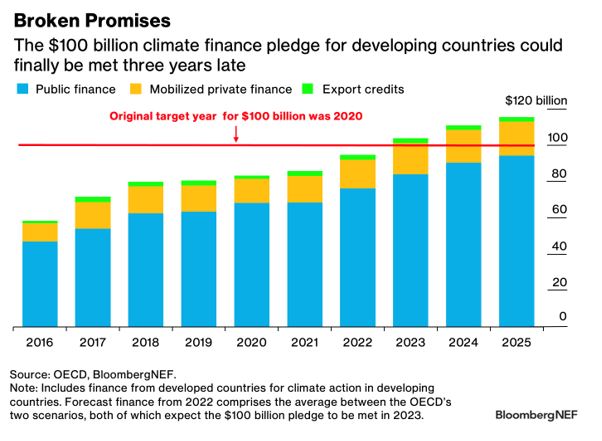

Developing countries are still waiting on the $100 billion of annual climate finance promised to them by wealthier nations back in 2009 – a commitment that was supposed to be reached by 2020 and that the OECD expects will be met three years late in 2023.

“They always say the right things, but they just don’t follow up,” Samaila Zubairu, president and chief executive officer of Africa Finance Corporation, told BNEF in an interview. “If we work together, we can find a way of making it happen – if it’s real. But if it’s not real, we’ll continue to do what can do by ourselves.

Cuming believes it is unlikely that developed countries will arrive in Sharm el-Sheikh with $100 billion. “So, a more constructive approach would be to agree on concrete steps to ensure they meet this threshold by 2025, as agreed in Glasgow,” she says. “This approach should make them accountable for non-delivery, which would build trust with emerging economies.”

But even if the $100 billion issue can be resolved, there remain questions over the types of funding, how it will be distributed and what will happen after 2025. That’s before even noting that a definition of climate finance has yet to be agreed.

The conversation is also shifting beyond mere financing of energy transition efforts to the idea of paying reparations for the loss and damage caused by global warming. Climate justice is expected to be near the top of the agenda at what has been dubbed the “African COP”, given that the region has played a minimal role in creating the climate crisis but is one of the most exposed to its harmful impacts.

It remains to be seen how receptive wealthier nations will be to these efforts. Last year, a proposal for an international loss-and-damage finance facility was blocked at COP26; instead, it was agreed that a dialogue on the issue would be held.

So far, only a few governments have pledged dedicated loss-and-damage funding and the amounts have been paltry. Denmark announced last month that it would provide 100 million Danish krone ($13 million) for this purpose.

3. Progress towards global carbon offset trading will need a jumpstart

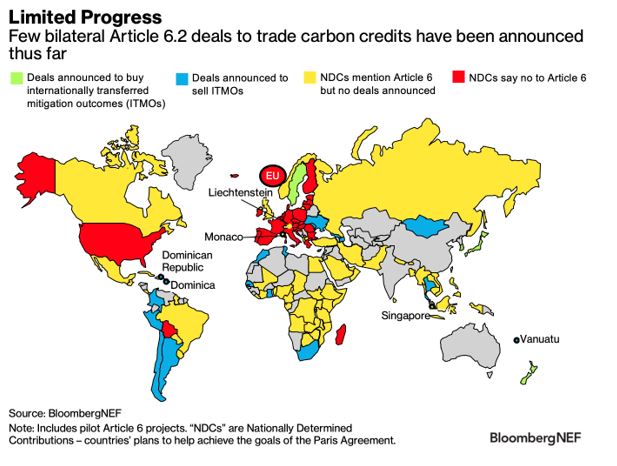

International trading of carbon offsets looked set to take off after governments agreed the principal rules for new carbon market programs, known as Article 6, at the COP26 summit. But only a handful of so-called Article 6.2 deals have since taken place, led by the likes of Switzerland and South Korea. These are bilateral agreements whereby offsets known as “internationally transferred mitigation outcomes” are generated by emissions-reduction or -removal projects and traded between countries to meet their climate goals.

Meanwhile, Article 6.4, which envisages a global carbon market in which credits can be traded by governments and private entities, is far from being brought to reality.

“There are two big barriers: expediency and quality,” says Cuming. “Parties need to make concrete progress at COP27 on the nitty-gritty details needed to implement the market within the next year or so.”

On the quality front, Cuming notes that voluntary carbon markets are “awash with offsets but a sizable share are from less environmentally robust projects.” A new global mechanism will need to “only include high-quality offsets that deliver credible carbon abatement.”