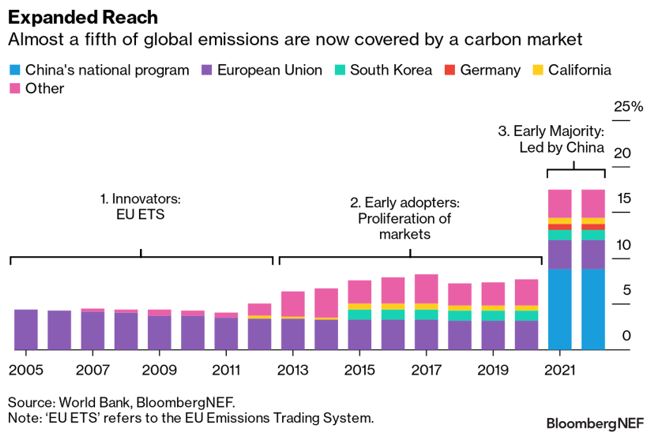

More countries are recognizing the value of putting a price on carbon as a means to achieving their climate goals. Close to a fifth of global emissions are now covered by a so-called compliance-based carbon market, up from just 5% a decade ago.

But while support for carbon markets is growing, mass adoption is still a long way off, with many of the world’s largest emitters remaining on the sidelines. Prices and ambition also need to be raised for these market mechanisms to play a substantial role in the shift to a greener future.

On the voluntary side, carbon offsets are gaining traction as corporations hunt for ways to neutralize their emissions, although the market remains hampered by oversupply and questions over credibility. Still, stricter regulation could enable voluntary carbon markets to take off in the coming decades and address any residual emissions that cannot be abated through other means.

Here are five charts from BloombergNEF on the untapped potential of global carbon markets.

1. Compliance markets broaden their horizons

The growing acknowledgment of the need to put a price on pollution has seen carbon markets established in more regions and expand in terms of both the volume of emissions covered and traded value. There are now 30 ‘compliance’ carbon markets operating around the world, in which entities must purchase or trade allowances for the emissions they produce. Together, these markets reached a value of more than $850 billion in 2021 and cover close to a fifth of global greenhouse gas emissions.

The European Union was one of the early innovators with the debut of its Emissions Trading System back in 2005, and momentum was turbocharged when China joined the party last year with the launch of its national market. But more countries will need to step up if the world is to make a serious dent in its emissions.

“A few key jurisdictions have yet to enter the fray, such as India and the US,” says Emma Coker, team leader for European carbon at BNEF. “While the US has some state-level schemes, which covered 8% of its emissions in 2021, a national US scheme remains unlikely. India has more recently discussed implementing a compliance carbon market but in the near term has decided to focus on voluntary schemes.”

2. More ambition is needed for real impact

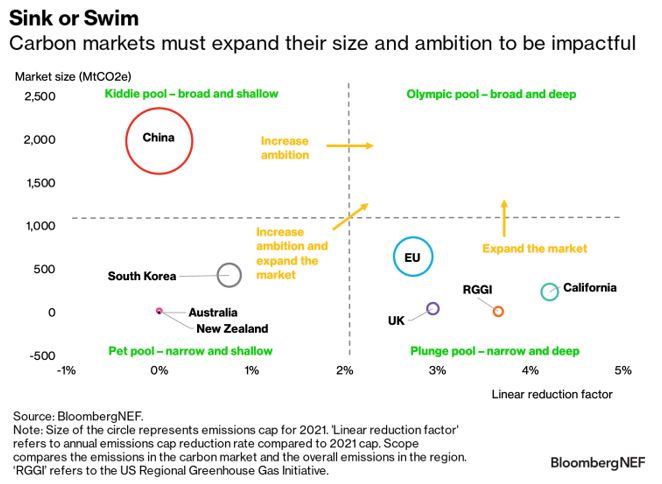

On top of the need for new markets, existing carbon pricing programs must significantly ramp up their size and ambition if they are to play a major role in decarbonizing the global economy.

“While some compliance carbon markets are undertaking sweeping reforms, there is still work to be done for them to advance from splashing around in a shallow pool to swimming in the big leagues,” says Bo Qin, lead analyst in BNEF’s carbon team.

BNEF considers a well-functioning carbon market, referred to as an ‘Olympic pool’, to be both broad and deep. This means it must have ambitious emission reduction goals and a large scope to enable the most decarbonization. None of the world’s major carbon markets have yet reached Olympic level.

“The EU could manage to achieve such a feat if the reforms under its Fit for 55 package are passed without being watered down,” according to Qin. “Meanwhile, the likes of China could push forward by increasing its ambition and creating a higher price signal to support abatement.”

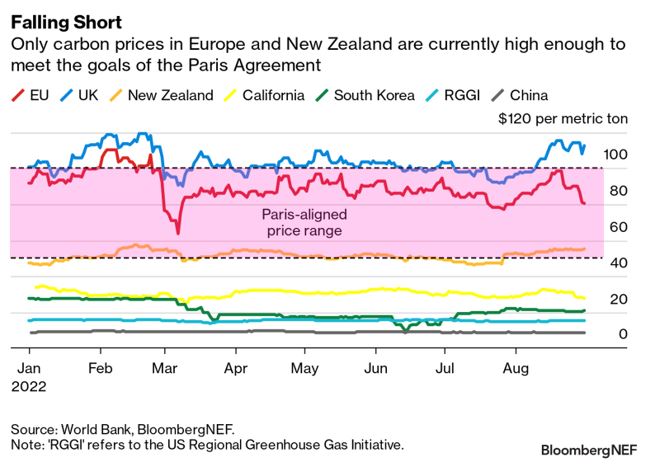

3. Higher prices are needed

While the proliferation of carbon markets is undoubtedly good news, prices are by and large still too low to have a material climate impact. This is particularly true for sectors outside of power generation where switching to low-carbon alternatives remains an expensive proposition.

The World Bank estimates that a carbon price of $50-100 per metric ton of carbon dioxide is required by 2030 to meet the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement – to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

However, only the EU, UK and New Zealand currently have prices within or above this range, with other major markets falling well short. Prices in China, the world’s largest market in terms of emissions covered, are languishing below $10 per ton of CO2. The laggards will require reforms to their market designs to reach the necessary price level.

“For many, this will involve tackling oversupply of allowances, both in terms of banked past allowance surpluses (for schemes that allow this practice) and reducing future allocation to encourage future scarcity,” says Qin.

But she also notes that the success of carbon markets is not just about reaching a certain price. “Alongside price levels, the salience of a carbon price is also key, whereby highly visible prices are more likely to result in behavioral change.”

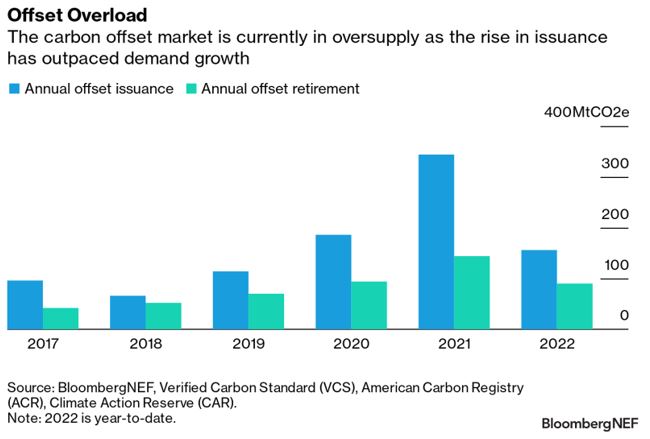

4. Voluntary markets gain momentum

The other side of the carbon coin is voluntary markets, whereby entities purchase offsets from projects that remove or avoid emissions to help neutralize their own environmental footprint.

Demand for offsets is accelerating. Over 144 million offsets were retired in 2021 – each corresponding to one ton of CO2 equivalent – up more than 50% from a year earlier.

“Despite corporate demand for offsets mounting as new net-zero targets are set, the market remains oversupplied with energy generation and avoided deforestation offsets – many of which are low quality,” says Kyle Harrison, head of sustainability research at BNEF. “Both of these factors have kept prices in the market extremely low, leaving corporations with little incentive to prioritize other decarbonization strategies.”

The supply-demand balance could shift quickly, as groups like the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) push for the use of only removal offsets to achieve net-zero emissions. Meanwhile, countries including Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and India are halting the export of carbon credits to help meet their own domestic climate goals.

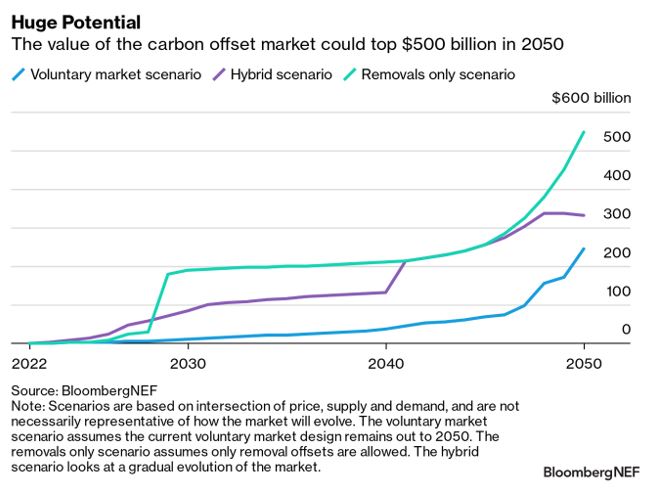

5. The next great commodity market?

Despite the hype of voluntary carbon markets, they are still very small compared to compliance markets, valued at around $1 billion to $2 billion in 2021. But their potential is huge, particularly as companies will likely look to offset any residual emissions in the coming decades after all other abatement options are exhausted.

In a scenario where only removal offsets are permitted, BNEF estimates demand for offsets could grow 40-fold between now and 2050, to 5.2 billion tons of CO2 equivalent, which is equal to 10% of global emissions today. Prices could reach $120 per ton in 2050.

“More stringent regulation around supply and demand could turn the offset market from the annoying little brother of the carbon world into the next great commodity market, valued at over half a trillion dollars,” says Harrison. “The work of various registries, independent initiatives and technology providers will therefore be key in the market’s development.”

There is also the potential for compliance and voluntary carbon markets to shift closer together, with seven major compliance carbon markets now allowing the use of offsets in some form and the COP26 summit laying the groundwork for global carbon trading to become a reality.