By Jade Patterson, Renewable Fuels, BloombergNEF

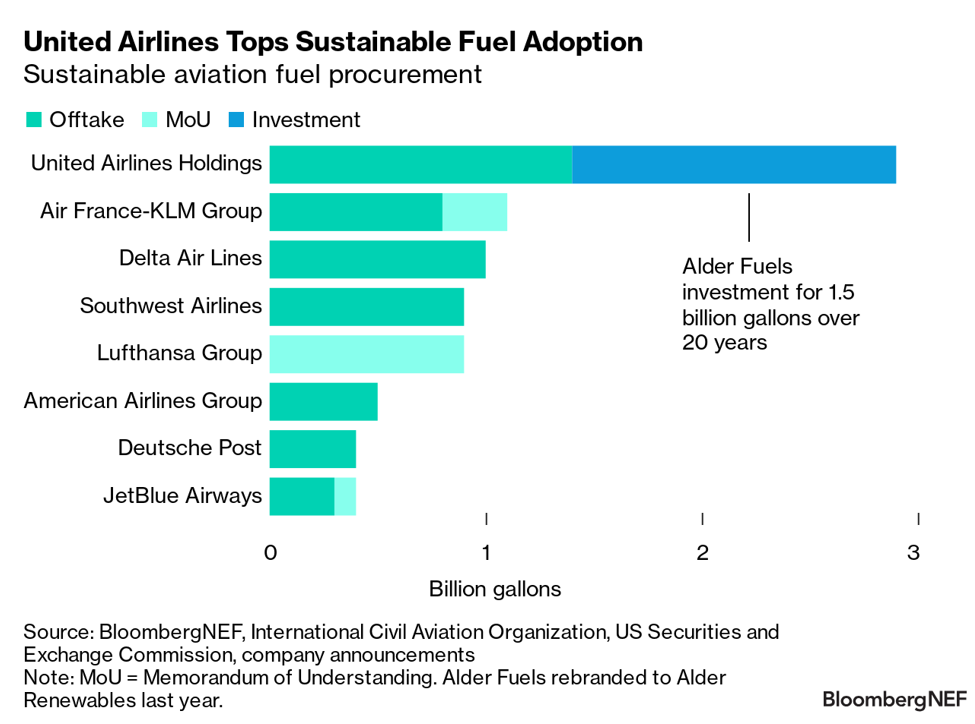

Green jet fuel, also known as sustainable aviation fuel or SAF, is priced two or three times higher than conventional fuel. Airlines are nevertheless procuring it to decarbonize operations, and United has emerged as the top buyer of the clean fuel.

It has secured 2.9 billion gallons of SAF, through offtake agreements and investments, putting it far ahead of any other airline, according to BloombergNEF data. This volume is to be delivered over varying timelines.

The airline is committed to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. United CEO Scott Kirby has disavowed “flashy, empty gestures” and has committed to the “harder, better path of actually reducing the emissions from flying.”

The airline is helping suppliers develop new feedstock supplies and novel production pathways through its investment arm, United Airline Ventures.

United announced, last year, a 1 billion gallon purchase agreement over 20 years with Cemvita, a biotech company working to develop microbes which can turn CO2 into lipids that can be used to produce SAF. United also invested in a company called Alder Fuels in 2021, which plans to produce SAF from biomass-like agriculture byproducts and wood residues using pyrolysis technology. The company was rebranded Alder Renewables last year.

Capacity boom

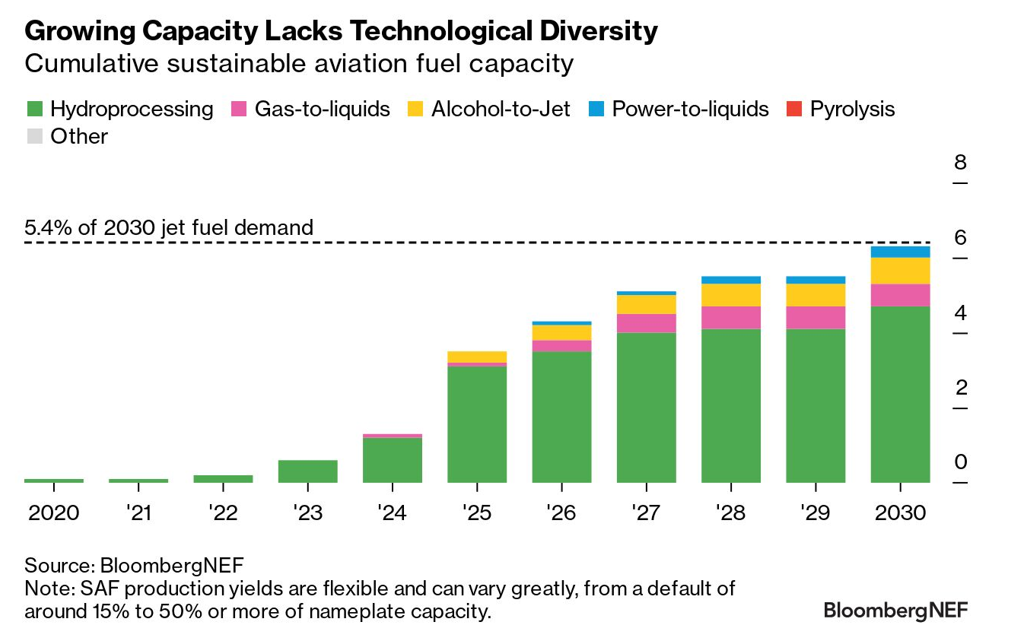

Global SAF production capacity is expected to increase 10-fold by the end of the decade, provided projects materialize on schedule and producers lock-in adequate feedstock volumes. It is expected to cross 6 billion gallons per year or 5% of total jet fuel demand by 2030, BNEF’s 2024 SAF Outlook shows. New developers and existing refiners such as Neste, P66 and Shell are constructing a slew of projects set to come online in the next couple of years.

Despite SAF’s momentum, feedstock constraints and high costs remain a challenge.

Airlines have signaled they are unwilling or unable to pay more for SAF than existing jet fuel due to tight margins and fear of losing market share to competitors. Policy initiatives are needed to cover the cost premium between SAF and conventional jet fuel.

SAF is challenging to scale as most production facilities rely on a process that uses waste oils and animal fats which are in limited supply. This hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids (HEFA) pathway can only meet around 4% of total jet fuel demand based on current feedstocks. Companies are working to develop new feedstocks or alternative production pathways but more research and development is needed to commercialize less established technologies.

(Added detail on rebranding of Alder Renewables in fifth paragraph and chart.)