By Adithya Bhashyam, Hydrogen, BloombergNEF

You know something big is afoot when competing lobby groups take out full-page ads about hydrogen in the New York Times and the Washington Post. Their ads aim to influence guidance issued by the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and Treasury defining how clean hydrogen can be produced.

This guidance could shape the emissions associated with billions of dollars in subsidies given to hydrogen. Originally expected on August 16, 2023, the delay in its publication shows how contentious this guidance is.

BloombergNEF’s view is that strict guidance is justified to maximize the emissions reductions achieved by using clean hydrogen, although with a transition period to help the industry grow.

The $70 billion question

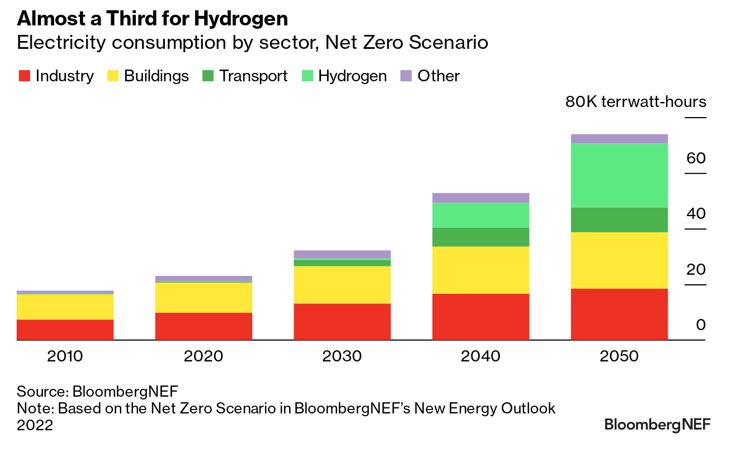

Policymakers around the world are setting up large subsidy programs to scale up the nascent clean hydrogen industry. Most prominent among these is the US Inflation Reduction Act tax credit for hydrogen, or ‘45V’, which promises up to $3 per kilogram of clean hydrogen produced over 10 years.

The subsidy is so generous that BNEF expects it to be larger than the cost to make clean hydrogen in the US by 2030. But its most lucrative characteristic is that it has no budgetary limit – every project that meets the greenhouse gas emissions criteria is guaranteed a subsidy. Based on the announced project pipeline as of September 7, 2023, subsidies given via the 45V credit could exceed $70 billion over the next decade.

This is likely an underestimate as the announced green H2 project pipeline would only cover a quarter of existing US hydrogen demand. In practice, more projects will be announced before the 2032 construction deadline for the tax credit and demand for H2 could grow beyond existing uses. Just replacing current demand with green H2 supported by 45V tax credits would require over $300 billion in spending, almost as large as the total spend estimate for the IRA.

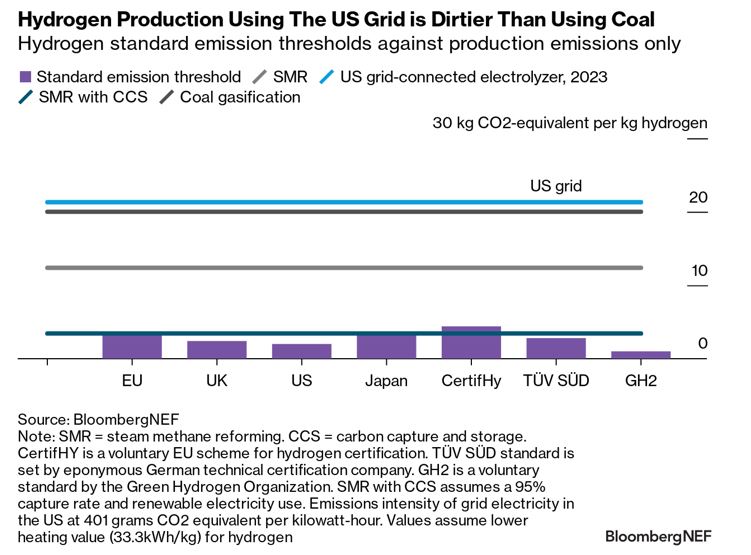

The billion-dollar question on developers’ minds therefore is how the emissions criteria can be met, particularly for electrolyzers connected to the electricity grid. The definition is likely to touch on three criteria:

-

New supply (‘additionality’):

H2 production can only buy power from newly built power plants rather than existing ones to incentivize additional clean power deployment.

-

Time matching (‘temporal correlation’):

H2 production can only happen at the same time when its specified power source is generating electricity.

-

Deliverability (‘geographic correlation’):

H2 production needs to be close to its electricity source.

A framework for US hydrogen guidance

The IRS and Treasury have a crucial role to play in this. Their guidance will determine whether over $70 billion in taxpayer money will go to producing molecules that cut or raise emissions.

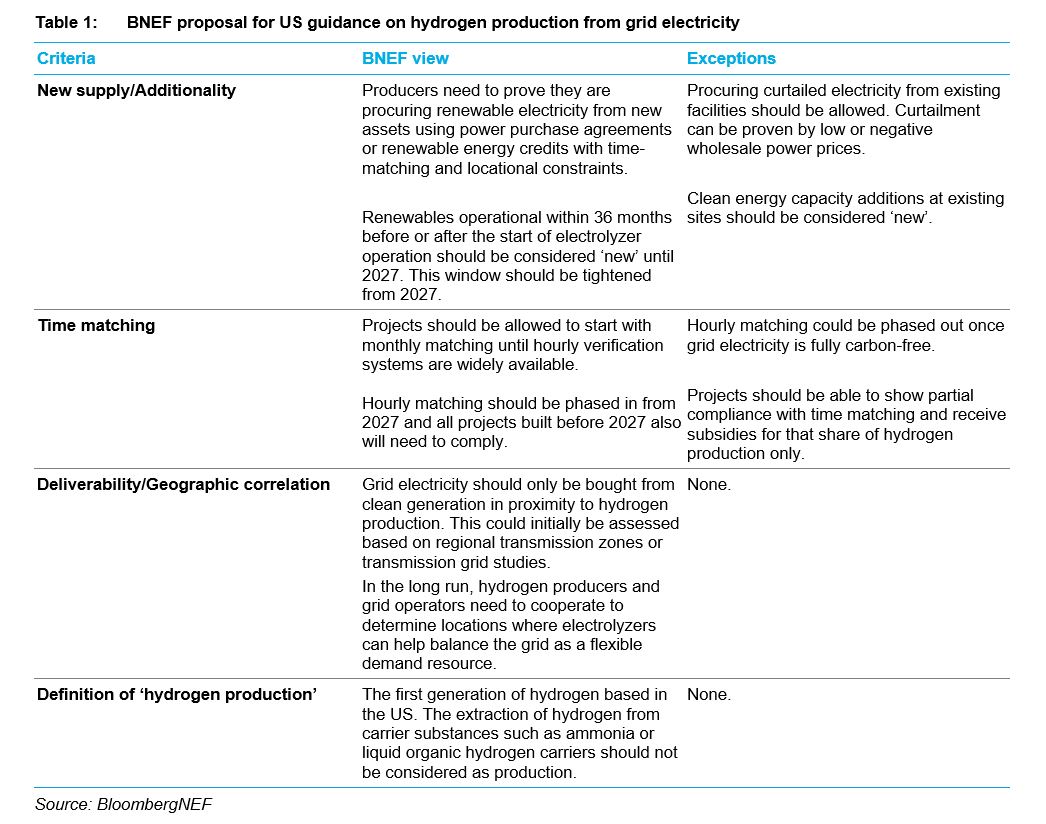

Guidelines for producing hydrogen from grid electricity will eventually require all three pillars of additionality, deliverability and time matching as guardrails to minimize emissions. But not all requirements can be implemented from the beginning as the technologies and systems to do so, for example for hourly matching, are not widely available. BNEF’s view is that the following guidelines would represent a sensible tradeoff.

-

Additionality with a 36-month window:

The constraint should apply immediately, however should allow electrolyzers to procure from clean energy assets that became operational within 36 months before or after first hydrogen production. This can be tightened to a narrower window by 2027 when more projects are expected.

-

Transition period from monthly to hourly time matching until 2027:

Projects in operation before 2027 can use monthly matching until 2027. This allows hourly verification systems to develop more widely and gives regulatory certainty to producers.

-

Deliverability from the start:

All projects need to avoid causing grid congestion by locating close to the generator they are sourcing electricity from and only in areas without preexisting grid constraints. This could initially be assessed based on regional transmission zones or the DOE’s Transmission Needs study.

-

Exceptions for curtailed electricity and new renewables capacity at existing sites:

Projects should be able to procure otherwise curtailed grid electricity without having to prove ‘new supply’. This could be shown by low or negative wholesale electricity prices which are below a price threshold at which only renewable energy generation is likely online. Enabling electrolyzers to use otherwise curtailed electricity also helps balance the grid. An increase in generation capacity at an existing site should also count as new supply.

Why 2027?

BNEF estimates clean hydrogen projects currently take around 3-5 years from feasibility study to operation. This includes a construction period of 2 years and 1-3 years from concept to final investment decision. Thus, most projects operational from 2027 should currently be in the design phase.

The 2027 transition period therefore allows projects close to an investment decision today to still go ahead without delays while giving time to later projects to incorporate stricter criteria into their design. It also enables hourly verification systems for time matching to become available widely.

BNEF expects at most 0.8 million metric tons of annual green hydrogen supply – or about 8% of today’s US H2 demand – to come online in the US before 2027 based on announced projects in BNEF’s Hydrogen Project Database as of September 7, 2023. These will have to take final investment decision by 2024 to make the 2027 deadline given current construction times. We, therefore, know exactly how many projects this guidance could affect early on and what their emissions impact will be.

The emissions impact of laxer criteria on early projects is likely small, especially if additionality and deliverability are implemented from the start.

Europe sets the precedent

Ultimately, only implementing all three criteria together will ensure low-emission H2 production. Implementing additionality and deliverability without time matching would not be enough.

Even if the US does not implement strict rules, US projects exporting to the EU, a lucrative opportunity due to potential import subsidies and greater profit margins, will need to comply with EU rules on H2 production anyway. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, once fully implemented, will also force hydrogen importers to reduce their product’s emissions due to penalties they would otherwise face.

Beyond these criteria, the guidance will also need to clearly define what terms like ‘hydrogen production’, ‘construction’ and ‘coming into operation’ mean. All of these are potential sources of uncertainty for producers and present possible loopholes to circumvent strict rules if defined loosely.

Implementing these rules in the US will certainly be challenging at first and the delay in the guidance shows how contentious the debate has now become. But, given the amount of money involved and the additional emissions that could be caused by lax rules, taking more time to implement carefully planned guidance is the right choice.

This publication is part of BloombergNEF’s Hydrogen Hypothesis Series. These reports tackle the important issues and challenges exposed during the scale-up of a clean hydrogen economy by taking a position on an important question facing the industry.