By Enrique Gonzalez, Head of Americas Gas Research, BloombergNEF

Warmer weather is impacting energy markets in a way that could put the energy transition at risk. US natural gas, for instance, is seeing increased demand from the power sector due to hotter summers. However, that is not enough to replace the large amounts of gas demand destruction caused by warmer winters, putting downward pressure on overall prices. In a future of continuous warmer-than-average winters, and cheap natural gas, the energy transition would face more challenges. Elevated green premiums would be harder to justify in such a situation.

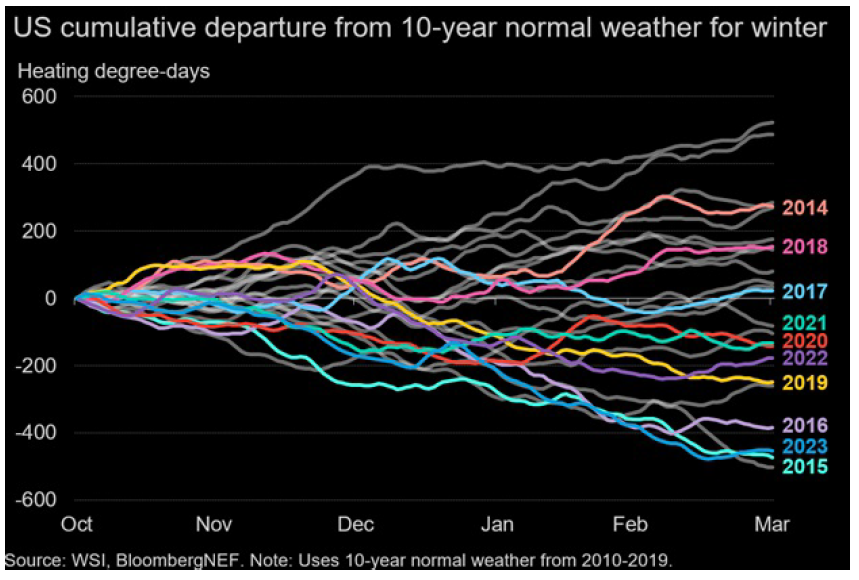

Global land and ocean temperatures have been rising and the US is no exception. When compared to the 10-year average weather from 2010-2019 (the zero line in the chart below), seven out of 10 latest winters have been warmer. This is reflected in the below average number of gas weighted heating degree days or HDD. These warmer winters cause significant gas demand destruction and put downward pressure on prices.

Rising temperatures also mean hotter summers but the gas demand gained from higher power sector consumption in the summers is not enough to offset heating demand destruction in the winter.

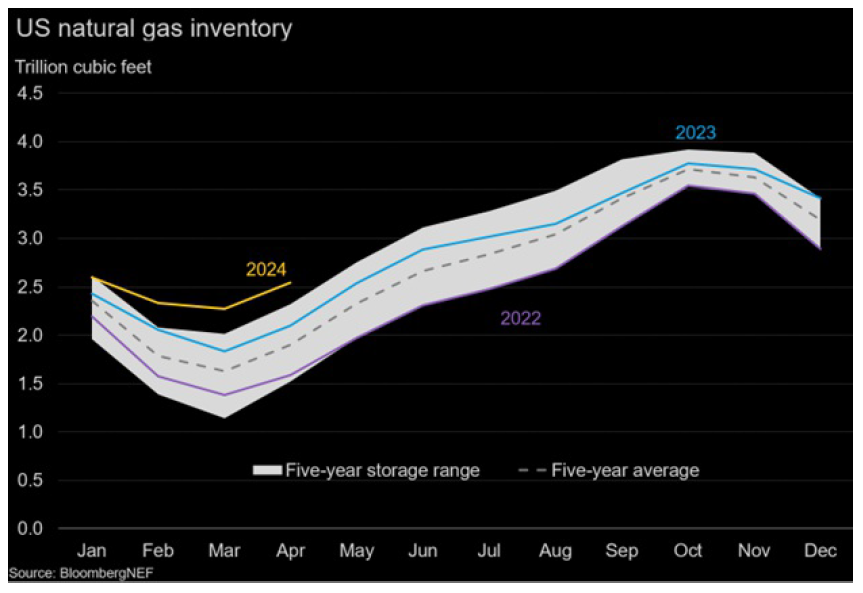

Winter 2022-23 and 2023-24 offer a glimpse into how a period that continually sees warmer-than-average winters can impact gas prices. Going into winter 2022-23, US natural gas inventories sat at the bottom of the five-year range while prices reached some of the highest levels since 2008. However, a considerably warmer than normal winter — alongside Freeport LNG being offline — pushed inventories above five-year average levels by the end of winter and dragged prices downwards.

The following winter started with inventories near the five-year average but was even warmer, some 454HDD below average, which ultimately pushed inventories above the five-year maximum while depressing prices to near pandemic lows. The dynamic poses an interesting challenge which can’t simply be approached by reducing inventories ahead of winter since the possibility of colder than average weather and higher demand is always open.

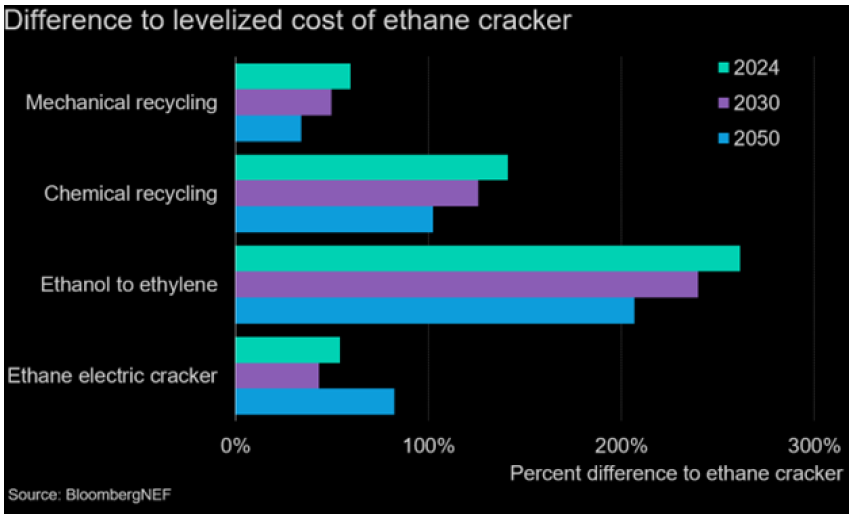

If warmer weather keeps gas prices low, the energy transition could become especially challenging in hard-to-abate sectors such as petrochemicals. In the production of ethylene, for example, which is used as feedstock to make polymers, plastics, and more, the green premiums of lower carbon intensive methods can become much higher.

When comparing an ethane cracker (gas derived feedstock), the premiums for greener methods of production sometimes surpass 100%, which makes less carbon intensive processes hard to justify. Under scenarios like these, it will be necessary to think beyond economics to execute a successful energy transition.