By Michael Liebreich, Senior Contributor, BloombergNEF

Rumors of the death of the transition have been greatly exaggerated, as I discussed in Part I of this article. In this second part, I want to lay out what a pragmatic reset in climate and energy strategy, one that responds to the current moment in history, might entail.

We saw in Part I that the world is at or near peak emissions. We saw that one in every five cars sold worldwide is an EV, and that the figure is one in two in China. We saw that clean energy and heat now supply just over 30% of the global energy services consumed by the economy. And we saw that, as long as clean energy continues to outgrow energy-service demand, fossil fuels will eventually but inexorably be squeezed out of the system.

At the same time, President Donald Trump is using every tool at his disposal to keep the US addicted to fossil fuels. And, like it or not, his actions are resonating in many other countries. The established consensus behind climate action is fracturing – it has crumbled in the US, was rescued from the brink by elections in Canada and Australia, shows severe strain in the UK and signs of cracking across Europe.

The climate and clean-energy community is facing a choice. It can remain reactive, doubling down on old narratives, pressing on with existing policies, preaching to the converted. Or it can undertake a pragmatic reset: Wind back historical over-reach, accept harsh realities, address legitimate concerns, refresh its offer and find new ways of communicating with a confused public.

I’m not going to write a manifesto. But I will present some ideas, intended to start a critical and perhaps overdue conversation about what a pragmatic climate reset might imply.

1. Reset climate politics

Job number one is to reset climate politics.

It’s easy to blame polarization on the oil and gas industry, libertarian think tanks and legacy media. The reality is that the climate and clean energy community bears its own share of the blame for this situation.

Stop talking down to people. Stop trying to make them feel guilty. Stop using implausible scenarios to scare them. Stop disrupting their commutes. Stop using the terminology of anti-Nazism to demonize them. Stop using climate and the environment to signal group membership, or to score political points. Above all, stop treating taxpayers and consumers like hostages at a cash machine – forced to withdraw savings in order to fund priorities they don’t share.

The transition will not succeed without the support of the sensible center. This is where most hard-working, asset-owning people reside, as well as the majority of executives and investors. These people are not “ignorant and inattentive” about climate change, to use the words of blogger and podcaster David Roberts, they are smart and concerned.

When someone says they think climate change is happening but it’s natural, or that there’s nothing we can do about it, or that whatever we could do would cost too much, or that only some imagined technology holds the answer, don’t misread them. Chances are what they are really saying is that they fear the current approach will lead to an increased cost of living, expansion of the state and the empowerment of unelected elites, and yet most likely still fail to solve the problem.

Looking around you, hand on heart, can you say these fears are unfounded?

Winning back the sensible center demands a new approach, focused on self-interest, fairness and harmony. Self-interest – that is, the knowledge that families can still prosper in a low-carbon world rather than crony climate capitalism. Fairness – the sense that injustices are being reduced and risks averted, not climate lawfare. Harmony – the feeling that the places we love, the society and cultures we grew up in, will endure beyond our time, in place of environmental fundamentalism.

To win the politics, stop taking the knee to Greta Thunberg and start worrying about energy bills.

2. Reset climate targets

Next, it’s time to put the decade of 1.5°C behind us.

A bit of history. Let’s go back to early 2015, a few months before the COP21 climate talks in Paris. Countries have agreed to limit the global temperature increase to 2°C but have not yet turned that figure into an emissions target. The UK – the most progressive economy in the developed world – was still targeting an 80% reduction under its pioneering 2008 Climate Change Act.

In June, the Group of Seven met in Schloss Elmau in Germany as guests of then German Chancellor Angela Merkel. When the closing communique appeared, it contained this bombshell: “We emphasize that deep cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions are required, with a decarbonisation of the global economy over the course of this century.” [italics mine – M.L.].

The political enthronement of net zero had begun.

But the enthronement went too far. The Paris Agreement only promised to “hold the increase in global average temperatures to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels”. However, in order to secure support from the coalition of Small Island Developing States (as documented in a series of Cleaning Up episodes), it also included a commitment to “pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels”.

This set in train a series of events, starting with the publication by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, of the SR15 report in October 2018, which documented for the first time the considerable climate impacts that could be avoided by remaining under 1.5°C. It also pointed out that keeping to 1.5°C would mean cutting emissions by 45% from a 2010 baseline by 2045 (around 50% from the 2018 figure) and reaching net zero by 2050.

These goals were immediately seized on by Fridays for Future, Extinction Rebellion, the Sunrise Movement and other activists, who were having their moment in the spotlight. Net zero by 2050 was adopted by politicians, executives and investors in an orgy of virtue-signaling ahead of COP26 in Glasgow. How many of them spared a thought for how much it would cost?

Energy and transport assets can have lifetimes of 30 years or more. Reducing emissions by half in the 12 years after 2018 would mean writing off trillions of dollars in productive assets, the economic impact of which was not captured in the IPCC’s analysis. What its report did show, however, as long as you scrolled to page 152 of Chapter 2, was the impact on marginal carbon prices: In the 2°C scenario they could rise to $225 per metric ton of CO2 (in 2010 dollars) by 2030; under 1.5°C they could go as high as $6,050 per ton. That’s quite the difference.

Adopting the 1.5°C target, therefore, meant targeting the premature retirement of a large slice of existing energy assets and throwing money at anything with the slightest chance of reducing emissions. Is it surprising that so many people now associate climate action with a profligate waste of public money and an elite indifferent to energy bills?

The irony is that the world went mad for 1.5°C at almost exactly the moment it became clear it could not be achieved: My first public statements that 1.5°C was no longer achievable can be dated to 2018.

Today, it is ten years since that G-7 meeting in Schloss Elmau. We have either passed the 1.5°C threshold or will do so in the next few years – yet commitment to 1.5°C still serves as an article of faith for the climate community. That has to change.

It’s not that 1.5°C of warming won’t have devastating impacts – indeed, we are already seeing them. But that doesn’t make it a credible target. Continuing to adhere to it leads to terrible policy decisions and undermines public support. It’s time to switch back to the hard 2°C target that lies at the heart of the Paris Agreement.

Coda I. To avoid exceeding 2°C of warming we still need to reach net zero, only later. Advanced economies would still need to target 2050; China would still need to target 2060; India would still need to target 2070 – just as they all promised in Glasgow in 2021.

Coda II: If we all get to within 5% or 10% of our targets, that’s pretty good going. If it’s not enough, we can always course correct along the way (following what is called in the jargon an adaptive pathway), using technologies and wealth generated over the coming decades. The target should be net zero-ish, rather than absolute net zero.

3. Reset energy priorities

When it comes to energy, the pragmatic climate reset means focusing on decarbonizing the first 90% as quickly and affordably as possible, rather than letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.

On one level, decarbonization is simple: Clean up electricity, and electrify almost everything. All low-carbon pathways ever modeled have this approach at their heart.

We already know how to electrify huge additional swathes of the economy at modest or no cost: Land transport, domestic and commercial heating, low- to mid-temperature industrial heat, and those thermal processes that can switch to electrochemistry. We even know how to decarbonize high-temperature industrial heat using commercially available technologies, particularly if we are prepared to pay a modest carbon price.

The challenge. A lack of skills, immature supply chains, reluctance to change behavior, existing high-carbon assets, lags in capital formation, lobbying and regulatory capture. These are all things that get fixed with the passing of decades and generations.

As for decarbonization of electricity, we certainly already know how to do this. Every country in the world is already doing it, even those with no commitment to climate action.

A decade ago, coal provided 39% of US power. Last year it was 15%. In the European Union, coal was at 26%, and last year it was 10%. The UK was 42% dependent on coal in 2012 and last year closed its final power station. In China, coal was at 73% of power ten years ago, in the first quarter of 2025 it was 58%. China may still be building new power stations, but it is also shutting old ones and using the ones it has less and less.

Over that same decade, wind and solar generation have soared by a factor of 18 – making them the fastest-growing new source of electricity in history, by a wide margin. This quarter, wind and solar together will deliver 17% of global power. Nuclear is growing too, but much more slowly. The global solar industry now has enough capacity to manufacture 2 terawatts of panels per year and will soon be installing 1TW annually – enough to replace 10% of fossil-based power.

The multi-decadal decline in solar and wind costs, only briefly interrupted by the recent spike in inflation, has resumed. Costs are below those of new-built coal or gas plants practically everywhere, and in many places below the cost of running existing plants.

Last year saw around 1 terawatt-hour of batteries manufactured, up by a factor of 26 over the past decade. To put this in context, 1TWh is enough to meet global power needs for around half an hour; models show that four hours of storage is enough for most grids to ride through most daily variations in supply and demand. EV batteries are increasingly being used to provide flexibility, and grid-connected storage is increasingly co-located with renewable generation. Ten more years of battery growth and the grid will be a completely different animal.

The main remaining challenges to complete decarbonization of the grid will be industry, seasonality and longer-duration resilience.

In countries with good resources, a combination of renewables with batteries will soon deliver dispatchable power more cheaply and reliably than coal or natural gas, so that’s a big chunk of industry sorted. Very sunny regions can already have power from solar and batteries 97% of the time at $104/MWh, down 22% from last year, according to estimates from think tank Ember. And Abu Dhabi is building the first GW of baseload solar in the world. Seasonality will most likely end up being solved by overbuilding (as happens in every other sector of transport, energy, infrastructure and the built environment).

This tide of cheap clean electricity is unstoppable. In the 11th century, after his failed attempt to stop the waters, King Canute declared that “all the inhabitants of the world should know that the power of kings is vain and trivial.” President Trump his Energy Secretary Chris Wright should take note.

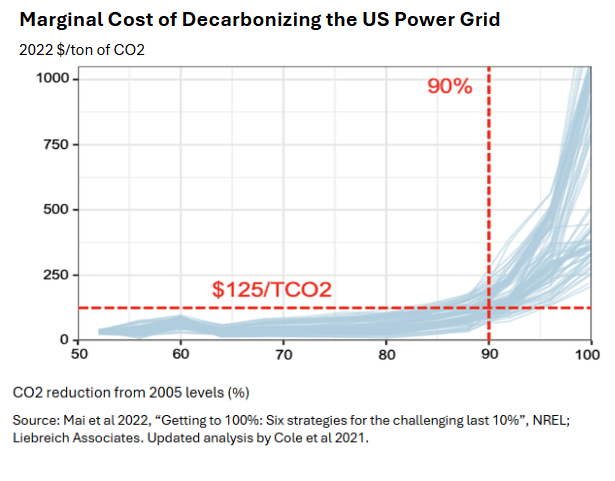

Then there is gas. In 2022, Trieu Mai and some of his colleagues at the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) showed that the cost of decarbonizing 90% of U.S. electricity would be around $125 per ton of CO2 (in 2022 dollars). After that it gets expensive, reaching $1,000 or more per ton to get to 100%. Similar results have been found for many other geographies including the UK, Germany and Australia.

I used to reject the idea of gas as a “transition fuel”. I was wrong.

If you simply replace big inflexible coal plants with big inflexible gas plants, you achieve an immediate halving of emissions, as the gas industry is fond of pointing out. The problem is, you are then locked in for the life of that plant and – given the scale of the infrastructure serving it – perhaps forever.

However, if you replace inflexible coal plants with flexible gas then, as long as regulation makes owners indifferent to the number of hours of operation, there’s no such lock-in. You might start with the flexible generation meeting 25% of the grid’s output, but as you continue to add very cheap wind, solar, demand response and batteries – and nuclear if you can get the numbers to work (see Part I for why I’m skeptical) – you can continue to push down gas use until your grid is 90% or more decarbonized. In fact, modelling shows that grids could keep going all the way to below 5% flexible generation before it becomes impossible to ride through periods of low renewable resources.

There is an additional benefit of leaving flexible gas capacity on the system: It can also help with grid stability.

The power cut that hit Spain and Portugal on April 28 was not caused by renewables. In fact, those who seize on power cuts (most recently Spain, but the UK, Australia, Texas, California, Chile and so on before then) as proof that grids must be based on fossil or nuclear power for stability, have been wrong every time.

Spain’s headlong rush to wind and solar, which were meeting 64% of demand at the moment of failure, had certainly reduced the amount of inertia on the system, but the issue that brought the grid down was the arcana of voltage oscillations. The fact is, Spain’s grid codes – the rules by which market participants feed in or draw out power – had not kept up with the rapidly-changing power mix; there was a culture of non-compliance by market participants; and too much was being asked of a weak interconnection to France.

It is perfectly feasible for renewable resources and batteries to provide grid stability services, and we should expect them to do so. Still, flexible gas capacity can help too, even at times when it is no longer needed to generate power. Engines and turbines can be decoupled from generators, leaving them spinning but neither consuming nor generating power. Then, when grid frequency changes, they provide inertia. They can also provide reactive power, short-circuit current, black-start capability and a range of other stability services.

Unlike a system that provides all grid stability services with only renewables and batteries, one with flexible gas generation can also ride through longer renewable outages at an affordable cost.

If society decides, at some later point, that we need to go all the way to a 100% decarbonized grid, we will face a well-defined challenge: How to replace a few percent of flexible gas generation (and the associated stability services).

Whatever route we choose, those last few percent would require vast investment and incur high running costs. It may be that by then we are so wealthy, and the impact of climate change so obvious, that we decide to spend the money. But it may be that we decide instead to do carbon removal, or to help laggard regions first. Or maybe we will have other priorities, like defense, or adaptation.

The fact is, how to decarbonize the last few percent of the grid is simply not a question we need to answer today.

Coda: Some sectors, of course, cannot be decarbonized via electrification – shipping, aviation, process emissions from cement, and the like. However, these account for less than 15% of emissions, and even here a pragmatic climate reset means focusing on rapid and cheap progress, not technological purity. 40% of shipping goes away if we stop shipping coal and oil around the world. For the rest, LNG, biogas and streamlined operations can reduce emissions far more rapidly than ammonia or synthetic methanol. Aviation emissions can be slashed via more efficient planes, improved operations, biofuels, contrail management and carbon removal, supported by appropriate taxation and the removal of subsidies. Industrial heat can be substantially decarbonized before tackling process emissions, which we will eventually eliminate via carbon capture and storage. We could finally get serious about plastics recycling or just accept that putting plastic waste in a well-managed landfill is a form of carbon sequestration. And so on.

4. Reset hydrogen

Hydrogen needs a reset all of its own. In all my decades as an analyst, I have never seen such a big disconnect between the physics of what a solution can deliver, and the politics of what’s being asked of it.

Why does this matter? Because if you wanted to delay the transition you would promote a solution that sounds perfect but doesn’t work. A fuel that is ubiquitous, easy to make, produces only water, will get cheaper and cheaper, provides jobs and photo-opportunities and solves every problem from cars to rockets, transport to fertilizer and steel to seasonal storage. Whoopee! And hydrogen even has an extra feature: It takes years and years to figure out that it is unaffordable – particularly if you can get the public to ignore 50 years of wasted public funds.

The hydrogen soufflé is beginning to deflate. At the end of last year, the European Court of Auditors found that the targets in the EU’s 2020 Hydrogen Strategy were “driven by political will rather than being based on robust analyses”, and called for a “reality check”. In January this year, France’s state auditor, the Cour de Comptes, estimated the country’s hydrogen strategy implies a cost of carbon of at least €520, and even jeopardizes France’s national finances.

But it’s time to go all in on the hydrogen reset. It is time to admit that green hydrogen will play no more than a bit part in a future low-carbon energy system.

It’s not just that green hydrogen is currently expensive to produce. It’s that it has no plausible pathway to affordability. Electrolyzer stacks will exhibit the same sort of learning rates as solar PV and batteries, but they are responsible for only around 10% of the cost of green hydrogen. Another 40% is electricity, and 40% is heavy engineering – electrical, chemical and civil – and their costs are not about to drop by the five to ten times required to make green hydrogen cheaper than other clean solutions.

You also have to add the cost of compression, transport, distribution, use and safety management. Even if your plan is to make ammonia locally from cheap wind or solar, or to feed hydrogen into a refinery, you either have to add the costs of batteries to smooth your power supply, or the cost of compression and buffer storage to meet the 24/7/365 demands of the downstream plant. If you are exporting, you’ll need pipelines and deep-water port infrastructure.

- Green ammonia? It could perhaps eventually be viable, but only where dispatchable green power is very cheap, natural gas is very expensive and there’s a local market for fertilizer (Brazil, China and India come to mind). Elsewhere, the numbers simply don’t stack up, not even for Saudi Arabia’s NEOM mega-project.

- Green steel? Simply not urgent. Switch primary iron production to natural gas direct reduction and you get 75% of the benefit at a fraction of the cost. We should keep working on direct electrical reduction and bio-coking coal, which promise to be cheaper and more flexible in terms of ore grades than hydrogen.

- E-fuels? No way will they ever be cheap enough to replace petrol or diesel or to compete with electrification. It’s obvious, really, because you can’t make something from electricity which is cheaper than electricity. Germany needs to stop the charade of Technologieoffenheit (technology openness) before it witnesses the implosion of its entire automotive industry.

- Hydrogen aviation? It’s a dead parrot, as even Airbus seems to have understood. Building the plane is not the problem (though it would carry half the passengers because it’s full of hydrogen and insulation) but there is no plausible way of getting liquid hydrogen to major airports at the required scale to run an airline.

- What about sustainable airline fuel made from hydrogen with captured carbon, or so-called e-SAF? According to the EU’s own figures, it currently costs 12 times more than jet-fuel. And, since it is made in chemicals plants with electricity as the feedstock, there is no plausible pathway to an order-of-magnitude cost reduction.

- Blending hydrogen into the grid? I have called this the stupidest idea from Stupidville, and I can’t improve on that. You are making a chemical feedstock for €6 – €10/kg, and then instantly reducing its heat value of less than €2/kg, while driving up costs to all other gas users, and committing to a pathway that cannot get beyond 6% decarbonization without building a new pipeline network. It beggars belief that this is being supported by governments – a gross failure of public policy.

- White (geological) hydrogen? At this point it its an interesting field for scientific research. It certainly exists, but probably can’t be extracted at a meaningful flow rate. Even if it can, unless it can be extracted at high purity it’s just slightly lower-carbon natural gas. If the resource isn’t big enough to last 40 years you can’t build a pipeline to get it to the point of demand, and if it won’t last 20 years you can’t even build a local fertilizer plant. Wishful thinking is not an energy strategy.

We need to decarbonize 100 million tons of current hydrogen demand, which causes around 2.3% of global emissions. Since green hydrogen will always cost at least $2/kg more than fossil-based hydrogen, that means finding $200 billion per year of additional money – equivalent to the entire global aid budget. And since you need 15-year offtake agreements to secure project finance, you are looking for $3 trillion of up-front, bankable support. That’s three orders of magnitude more than anything available today.

The only affordable approach to decarbonizing current use cases is by means of hydrogen from natural gas, with the carbon captured and sequestered. Of course we have to do it right: Limiting fugitive methane emissions to less than 0.2% and achieving 95% or more capture and carbon sequestration. Society needs to demand that producers meet these stringent targets, instead of falling for activist claims that they are physically unachievable.

Coda: Luckily, there’s a silver lining to the inevitable failure of green hydrogen – it will be a relief for the planet. Every wind and solar project developer has to decide whether to sell electricity or make hydrogen. Until such time as the world is awash with green electricity (or pink, from nuclear, for that matter), every kilowatt-hour used to make hydrogen could deliver two to nine times the emission reductions if used directly, at a fraction of the cost. So that is what the pragmatic climate reset demands we do.

5. Reset diplomacy

In November 2011, I wrote a piece for BloombergNEF called Ya Basta! Time to Call Time On The COP Show. My argument was that the failure of 17 COP meetings to produce a global deal was actually harming the meteoric rise of clean energy that BloombergNEF was chronicling. Four years later, at COP21, the Paris Agreement was signed and, in a piece entitled We’ll Always Have Paris, I had to admit that “in retrospect I am very glad no one listened to me!”

I am older and wiser today so I am not going to call for the UNFCCC or even the COP process to be abandoned. But climate diplomacy most certainly needs a pragmatic reset.

My own first experience of COP meetings was COP14, Poznan, 2008. When I turned up, a subcommittee of the 9,000 delegates was debating whether to reopen the previous year’s agreement on the position of a comma. I kid you not. They were still at it a year later at COP15 in Copenhagen. There, the 27,000 delegates famously enjoyed freezing weather, poor food, traffic jams and huge lines, and produced… nothing of measurable benefit to the climate.

Back in Poland for COP19 in 2013, the hosts enraged the activist community by inviting businesses – including Polish coal-producing ones – to participate. By 2015, COP21 in Paris, side-events were everywhere, and delegate numbers had swelled to 30,000. COP26 Glasgow in 2021 saw 38,000 delegates (of which an undisclosed proportion caught Covid-19) at what I would argue was only the second breakthrough COP in history (Paris in 2015 being the other).

The three COP meetings since then have been hosted by oil and gas exporters Egypt, UAE and Azerbaijan. COP28 in Dubai was the UNFCCC’s Woodstock, with 84,000 delegates. We spent much of the week stuck in taxis, checking on our phones to see if the world would pretend to “phase out” unabated fossil fuels or only pretend to “transition away”. After decades of negotiations, a loss-and-damage fund was agreed – raising less than 0.1% of the market value of Saudi Aramco.

Last year’s COP29 in Baku was held in the shadow of President Trump’s re-election promise to exit the Paris Agreement for a second time. Instead of acknowledging reality, leaders of the Western democracies promised to invest $300 billion per year in developing countries by 2035. What were they thinking?

The COPs simplistic rich country / poor country classification is stuck in the last century. Today, supposedly rich countries are full of people suffering economic hardship from stagnant incomes, a cost-of-living crisis, persistent inflation, low growth and an ongoing European war. Meanwhile many supposedly poor countries (Non-Annex I Countries, in COP-speak) have skyscrapers, space programs, global multinationals, oligarchs owning European football clubs, middle classes taking international holidays, and millions of kids attending Western universities.

It is astonishingly tin-eared for Group of Seven leaders to fly off to Baku and promise to invest hundreds of billions of dollars per year in their emerging economic rivals – receiving nothing but a handful of climate indulgences in return.

The single best thing developed countries can do to ensure the decarbonization of South Africa, Indonesia or wherever, would be to succeed in decarbonizing their own economies while preserving their population’s standard of living. Do that, and the whole world will follow. Fail, and no amount of conferences or communiques on North-South climate finance will make any difference.

So, what would a pragmatic climate reset of the UNFCCC/COP look like? A full answer would require more words than you want to read. But here are some ideas:

- Host the annual meeting on an island with no more than 5,000 hotel rooms, and a broader meeting only once every five years. Demand that delegations be led by ministers of finance, energy or trade rather than ministers of environment or climate.

- Stop pretending plenary decisions are binding. Move from consensus to qualified majority voting. That alone would shorten meetings from two weeks to one.

- Focus on sectoral deals in industry, energy and transport, rather than economy-wide agreements. Move land use, land change and forestry, or LULUCF, into its own Convention: the social, cultural and political importance of land means no government will ever let the tail of climate negotiations wag the dog of national priorities.

- Shut down the loss-and-damage track. It makes no sense to build a duplicate aid infrastructure, particularly when losses cannot be unambiguously linked to climate change. Climate models which cannot predict individual storms, floods, fires or droughts cannot be used retroactively to quantify the contribution of climate to their cause – no matter how many activist scientists tell you they can.

- Nearly 20 years ago, I wrote a piece explaining that climate change is not a simple prisoner’s dilemma but a repeated, multiplayer prisoner’s dilemma, which means the winning strategy is be to be “nice, retaliatory, forgiving and clear” and the role of the UNFCCC is to act as coach and mediator. It needs to focus on creating platforms for sectoral, bilateral and multilateral negotiations – not trying to deliver global economic government by means of emissions policy.

6. Reset science

In 2018, I launched the hashtag #RCP85isBollox to draw attention to the implausibility of the worst-case scenario used throughout climate research. Two years later, climate scientists Zeke Hausfather and Glen Peters published Emissions – The ‘Business As Usual’ story is misleading, agreeing that RCP8.5 needed to be retired. And yet RCP8.5 (and its modern analog SSP5-8.5) remains the most popular scenario in the climate literature, even today. This is a scandalous failure of science to self-correct.

The reason I made such a fuss about RCP8.5 was that it creates a trivially easy attack surface for opponents of climate action. And, sure enough, in his Presidential Order “Restoring Gold Standard Science”, President Trump specifically named RCP8.5, citing academic research from 2017 that showed how reaching it would involve burning more coal than exists in the world’s recoverable reserves. On this matter, though it pains me to say it, Trump is right.

Another case in point is the Critical Review of Impacts of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, the report by five known climate sceptics intended to serve as the evidence base to revoke the EPA’s Endangerment Finding. There is much to criticize about the report, without doubt. However, it should also be noted that the original Endangerment Finding was based on research dating to before 2009, using scenarios even more extreme than RCP8.5. No one committed to science-based decisions should object to a review, in light of another 15 years’ worth of additional research and data. The focus should be on making sure the review is objective – in which case there seems little doubt the Endangerment Finding would remain in place – rather than rejecting it out-of-hand and claiming that it is entirely and completely without merit.

Today, the IPCC is about to sign off on a new set of scenarios to be used for its next Assessment Report, AR7, due out in 2029. Despite stipulating that its scenarios must be plausible, the IPCC imposes no peer-reviewed test of plausibility. The worst-case scenario which they are about to endorse (SSP3-7.0), is no more plausible today than RCP8.5 was seven years ago. I am afraid this suggests the failure to self-correct is not accidental, but intentional.

The pragmatic climate reset does not mean dismantling the entire edifice of climate science, but reforming it. IPCC scenarios really must be plausible from an energy systems perspective. And they must focus on the landing zone to which we might actually be headed – between the 1.8°C which would still count as “well below 2°C of the Paris Agreement, and the 3.5°C that is now the plausible worst case (and which US Secretary of Energy Chris Wright says would be fine and dandy, based on the modeling by William Nordhaus which won him the Nobel Prize).

Above all, scientists need to stop trying to scare people and focus on informing them. Let society do the rest.

7. Reset finance

The pragmatic climate reset also means rethinking the role of sustainable finance. The idea that you can squeeze CO2 emissions out of the real economy or achieve environmental goals by means of financial regulation and central bank interventions has been tried and found wanting.

At COP26 in Glasgow, no fewer than 60 multilateral organizations were promoting the use of finance as a way to bend the arc of the global economy toward net zero. Towering over them was the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, whose members managed assets worth $130 trillion.

It didn’t work. Threats of legal action led to the withdrawal of major names and a severe pruning of the thicket of organizations and initiatives. In late 2024, a US coalition of Republican states launched lawsuits against leading asset managers – later joined by the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission – claiming that they were violating antitrust and consumer protection laws and using ESG issues as a way of driving up energy prices in order to boost their investment returns.

Even in regulation-loving Europe the tide has turned against ESG. Just as I warned in 2021, the EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities turned out to be “a considerable over-reach”, and attempts to get asset managers to report on Scope 3 emissions were “simply a mess”. Last year, after complaints of excessive bureaucracy from France, Germany and other countries, the European Commission and the European Banking Authority were forced to hack back reporting requirements.

The whole edifice of ESG has descended into little more than a box-ticking exercise.

While it may be possible to identify the lifecycle carbon emissions of a single product or project, when it comes to a company or investment portfolio, it is impossible. I’ll give you one example. How would the investors in New Energy Finance have rated the emissions impact of the initial million pounds raised in January 2006? We were using grid power in the office, most of which was from coal and gas, and flying to conferences and client meetings. Not good. However, over the next 20 years, New Energy Finance (now BloombergNEF) became the most trusted information provider to investors pouring trillions of dollars into climate solutions. That first million pounds may have been the single most effective climate investment in history – yet not one of today’s ESG methodologies would have given it a pass mark.

We need to get back to basics.

- Companies are not vehicles for delivering social outcomes or justice. They are vehicles to produce products and services valued by customers – while respecting the spirit and letter of the law, generating returns for investors, and treating their staff and other stakeholders fairly. There is no evidence that becoming a so-called B-Corp improves behavior.

- Asset managers allocate capital into well-run businesses, provide custodianship on behalf of asset owners and beneficiaries, and treat all other stakeholders fairly. Investment regulation needs to align with those goals and stop trying to save the world.

- Policy makers need to stop using the financial system to discriminate against organizations active in politically unpopular parts of the economy. If they want different outcomes, they need to l regulate the real economy.

- Activists too – stop claiming oil and gas companies cause emissions (especially if you yourself haven’t yet switched to green power, electric heating and no-fly holidays). We are all the cause, and we all have to be the solution.

- It’s time to retire the term ESG. Once you get beyond issues of basic fairness – which is delivered through strong leadership, a healthy corporate culture and robust HR processes – ESG is all about nothing more than risk and opportunity. Every board and management team needs to understand the full set of issues that could destroy their business or present extraordinary opportunities. The fact that some may stem from environmental, social or governance factors does not justify a different department. Fire the consultants and box-tickers. Reassign the corporate sustainability officer. Focus on the issues, not the process.

- The role of central banks is to maintain sound money and a dynamic, flexible economy. It is not their role to ensure the country meets environmental, social, industrial or other targets – that is the role of government. If political leaders fail to create appropriate regulations to enable capital formation around desired solutions, it is not up to central banks to second-guess them.

8. Reset policy

The pragmatic climate reset also means a new approach to policy and regulation. Here are a few thought-starters:

- Remember what we learned in Part I: If clean energy grows 3% faster each year than total demand for energy services, and keeps it up for decades, fossil fuels will be squeezed off the system in a time-frame broadly consistent with 2°C. The overwhelming priority is to maintain growth in clean energy, year in and year out.

- Policies designed to restrict investment in fossil fuel supply are a recipe for energy price inflation and social pushback. Without investment, global oil and gas output would decline at over 10% per year. With investment in existing fields alone, the decline would still be 4% to 6% per year. Once clean energy can meet demand growth, fossil fuels will be pushed off the system, but until then, climate justice demands that we let them keep energy costs down and the public on board.

- All new climate-related grants, subsidies and regulations need to pass a value-for-money test, based on cost per ton of CO2 avoided. The calculation must include the contribution of overlapping measures, to make explicit the impact of multiple subsidies, and should be repeated at five-year intervals.

- For solutions that are competitive with fossil fuels – including relevant carbon prices – policies should focus on removing barriers, not on providing funding.

- Solutions that are not yet competitive may still deserve funding or regulatory support, but only if they can demonstrate a plausible pathway to a carbon price of $250 per ton within a decade – which must be peer-reviewed and published ahead of any funding decision.

- Solutions that cannot meet the “plausible pathway to $250/tCO2 in a decade” value-for-money test may still receive funding, but only for R&D or pilots. They are simply not ready for prime-time and must not receive funding or regulatory support for scale-up or roll-out.

- Investors who disagree with the findings of the value-for-money test are welcome to invest their own money and come back later with better evidence of a cost-reduction pathway.

- Each measure providing public funding or creating a regulation-driven market must include a sunset clause. If it does not deliver as promised, if it is not on track to deliver the expected cost reductions at any five-year milestone, the measure should automatically be suspended.

- Any mechanisms supporting asset investment needs to focus on the point when assets are reaching their end of life and need to be replaced anyway. There is a huge cost difference between replacing a fully-functioning boiler, car, power plant or piece of industrial equipment, and one that is fully depreciated. If no one were ever again to purchase a fossil-burning asset, the world would be on track to net zero in one asset cycle. Think about it.

- Public statements relating to the cost of climate action need to differentiate carefully between total investment, additional investment, and actual costs. Too often, total investment is presented as a cost, ignoring the fact that investments have a financial return, and that investment would also be required in any fossil-based counterfactual. The actual cost of climate action to consumers is usually a fraction of the total investment, and often even negative, and it’s time for that story to be told – loudly and clearly.

- Stop promoting fossil fuel consumption. There is a rich literature on fossil fuel subsidies, most of it worthless because it confuses subsidies with non-cash externalities and gives fossil fuels no credit for the royalties and taxes they generate. Just do the simple stuff: Stop cash subsidies, insulate homes instead of giving people fuel allowances, stop giving freebies to airports and tax breaks to airlines in the belief that they are magic machines for economic growth.

- Shift green levies and social charges from clean to fossil-based solutions and in particular from electricity to gas. The biggest single barrier to electrification is the difference between power and gas prices. One example: with an electrical heat tariff no higher than three times the gas price, any heat pump with a coefficient of performance of three or more would reduce utility bills. No further policy would be required to drive their uptake.

- Embrace locational pricing. The reason cheap renewables reached grid competitiveness in 2015 was not just falling production costs, but also because the world adopted reverse auctions. It is time for another major shift – to locational pricing. As soon as the penetration of variable renewables gets to the point that grids struggle, locational pricing matters. Incumbents hate it – they would rather be paid wherever they build wind and solar, whether it is generating or curtailed. Locational pricing shifts value from the supply side to the demand side and is essential to maintain public support for the continued growth of clean energy.

- Reform the Greenhouse Gas Protocol carbon-accounting rules. The current ones, written in 1990, allow companies to claim they use 100% renewable power on the basis of annual matching – which means they can offset night-time coal use with extra purchases of daytime solar power. It’s absurd and destroys public confidence. The rules are currently under review and need to be tightened.

Summary – the Climate and Energy Reset

I said I was not going to write a manifesto. The ideas here are intended as a provocation. Some of them might make you uncomfortable, in which case I apologize. Some of them make me uncomfortable. But this is surely a moment for frank talk, given what is going on in the world.

If the climate and clean energy community wants to do more than hunker down and watch brick after brick being kicked out of the foundations of the future clean energy economy, it needs to take control of its destiny. Refresh its offer, scrape off the barnacles, and come out fighting.

A pragmatic climate reset is essential if we are to maintain momentum toward a low-carbon economy over the next few years. The transition is dead. Long live the transition!