ARTICLE

Progress Despite Fragmentation: The Energy Transition to 2030

The second half of the decade will not be straightforward, but count on more progress being made.

By Albert Cheung, Deputy CEO, Head of Global Transition Analysis, BloombergNEF

The emergence of a lower-carbon global economy, at the core of which is the energy transition, encountered many challenges last year. The start of 2026 is unlikely to bring the sort of reset that climate-focused investors and companies might like to see. Following this troubled time it is important to understand how the context has changed around the world, and why energy transition will continue to progress, in spite of ongoing challenges.

Different regions, different priorities

A year ago, I wrote that the over-arching narrative for low-carbon transition had shifted from one of opportunity to one of competition. This shift is even more evident today – indeed, it is no longer clear that major economies are even running the same race. Different priorities are leading to fragmentation.

In the US, the race for clean energy leadership has been subjugated to the race for AI dominance, a competition in which the US still leads. This is super-charging demand for both clean and fossil energy to power an explosion of data centers. On the international stage, American diplomats are now leaning into their country’s role as the world’s largest oil and gas producer, searching for more LNG markets and actively disrupting efforts to decarbonize shipping. More recently, US action in Venezuela shows just how radically its priorities have changed.

For China, energy security and clean energy leadership continue to coincide as both strategic priorities and economic growth drivers. In China’s case, these priorities sit alongside the quest for AI dominance. The country’s success in EVs means domestic oil demand has already hit a peak, helping to limit its exposure to fuel imports. The might of its renewable energy sector, meanwhile, suggests a peak in coal (and therefore emissions) may be at hand. China’s clean-tech companies continue to grow their businesses overseas through both exports and international manufacturing investments – even though tariff barriers, stubborn over-capacity and project delays are causing pain.

Europe, meanwhile, retains its role as a global climate leader. This is despite a softening stance on sustainability disclosures and vehicle emissions in the EU. In a more uncertain world, clean energy and electrification continue to offer the EU and UK a path to greater energy security and reduced exposure to international oil and gas markets. The greater challenge facing Europe is how to increase its economic competitiveness in a world dominated by Chinese-made products and American information technology. Lower energy prices must be part of the solution. And reduced LNG exposure could be one factor that will help.

Each of these major economies faces different strategic considerations, and climate mitigation is no longer the shared priority it once was. Nowhere is this clearer than in the mixed bag of so-called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) submitted last year, in advance of COP30. The UK and EU have each set new Paris-aligned emissions goals for 2035, which will require significant efforts to achieve. China’s new target is a step forward as for the first time it calls for the country’s emissions to decline, even though it lacks quantitative ambition and should prove easy to reach.

In contrast, the US’ NDC, released in the last days of the Biden administration, is now effectively null and void (the US is exiting the Paris Agreement). India, another major player in the global energy and emissions picture, has not even submitted one yet.

These decidedly mixed approaches to emissions goals should go down as the legacy of international climate action in 2025 – demonstrating how changing priorities have knocked climate progress down the priority list.

Clean energy will keep making progress

All of this provides for some awkward mood music, but the energy transition keeps on trucking, and we will see more progress in the second half of this decade.

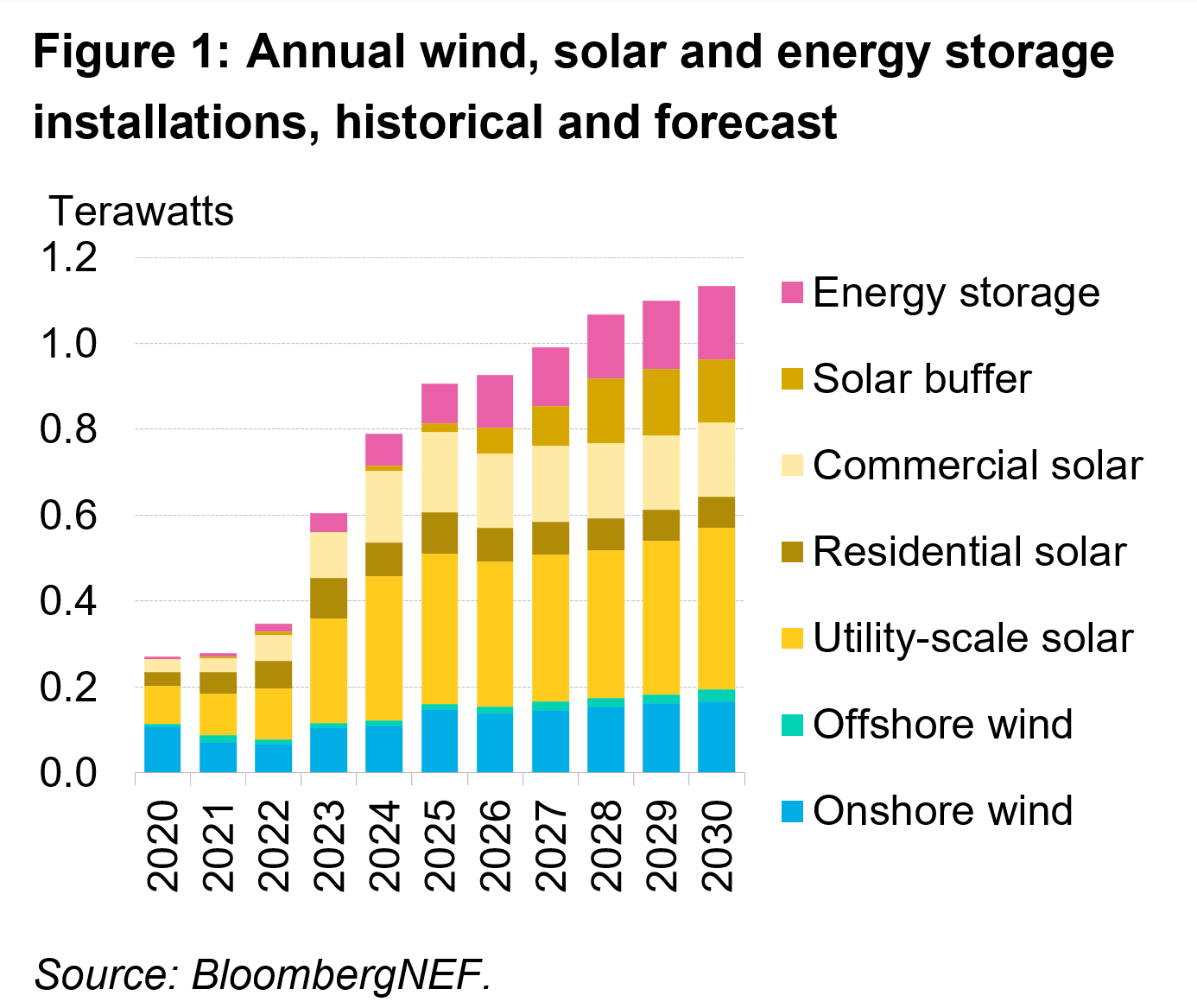

Take renewable energy. We estimate that global solar and wind installations exceeded 800 gigawatts last year — an all-time record and a tripling in yearly deployments since 2021.

Installations will be flat in 2026 and grow more modestly to 2030 – but they will grow. As we have said many times before, the economics of renewable power are just too good to ignore, and this helps to insulate the sector from geopolitical volatility. What is more, the acceleration in power demand from AI data centers and electric vehicles will undoubtedly support further deployment of wind, solar and storage, even in the face of changing tariff regimes.

Globally, we now expect 4.5 terawatts of new wind and solar installations over the next five years – a 67% increase on the preceding five-year period. Even in the US, where policy momentum has moved decidedly away from clean energy, we still expect some 336GW of wind, solar and energy storage to be installed in the years 2026-30. This is a significant reduction from our previous forecasts but is still 24% higher than installations in the preceding five-year period.

Speaking of energy storage, the future here looks bright too. We expect annual global storage installations to exceed 100GW in 2026 for the first time and rise onward past 200GW over the coming decade. Our most recent Energy Storage System Cost Survey showed that equipment prices are now $117/kWh – less than a third of what they were three years ago. This tipping point is arriving just in time to support continued renewable energy growth in markets where power prices have been depressed by high solar penetrations.

Disruption under way as EV growth continues

Falling battery prices, and better electric vehicles, continue to drive electrification in transport. EV sales are now over a quarter of global car sales – an unthinkable milestone just a few years ago – and we are forecasting their share to rise to 40% by 2030. China is the runaway leader, with EV share of over 50% today, and Europe’s share is above 25%, while other markets sit below the global average.

True, not everything in life is about economics, but quite a lot of it is. It is no coincidence that China is the only major market selling a majority of EVs – it is also the only major market where upfront purchase prices of EVs have fallen below the price of an internal combustion engine vehicle. In other markets, there is still an EV premium, but we should expect sales to keep rising everywhere as that premium narrows. This includes emerging markets, where we are seeing strong growth, such as in Southeast Asia, Latin America and even Ethiopia.

The rapid development of EVs in China means that incumbent Western and Japanese automakers face disruption. The market share of foreign automakers in China has fallen from two-thirds in 2020, to below 40% today. At the same time, Chinese automakers have seen a step up and now command an 18% share of EV sales in markets outside of China (with Europe being one of the main destinations).

While US federal policy makers seem to have made peace with ceding the global EV market to China, European leaders and automotive companies are determined to fight on. The industry is increasingly collaborating with Chinese companies to accelerate their battery and EV technology development. Examples include Stellantis’s partnerships with CATL and Leapmotor to produce batteries and EVs, and the partnership between Volkswagen and Xpeng to jointly develop EV models for the China market.

The European Commission’s recent decision to weaken its 2035 vehicle emissions policy will allow internal combustion engines to keep being sold in the EU after that date, but we still expect more than 80% of new car sales will need to be pure battery-electrics by then, which provides a clear growth signal for the sector.

Disruption is also on the way for global oil markets. Our base case scenario has oil demand peaking in 2032, as EVs shave more barrels off the global market. (This is in contrast to the IEA’s recent World Energy Outlook Current Policies Scenario, which projected rising oil demand until 2050). The year of peak oil has moved around in BNEF’s forecasts over the years, but even a sharp reversal in US climate policy has only shifted the milestone back by a year or two.

Hard-to-abate sectors are still hard, but progress is being made

Beyond clean power and vehicle electrification, momentum is more fragile. The decarbonization of industry, building heat, shipping and aviation relies on technologies which today are out of the money and still scaling up. The ingredients for success are, however, well understood: technologies such as electrification, hydrogen, carbon capture and renewable fuels need robust carbon pricing to level the playing field, subsidies or incentives to defray additional costs, mechanisms that create demand and – if appropriate – trade protections to prevent carbon leakage.

This year will deliver important lessons on how to make these measures work. The EU is introducing its long-awaited (and dreaded, in some quarters) carbon border adjustment mechanism, or CBAM. Coupled with its decarbonization bank and the phase-out of free allowances in the carbon market, this is, in principle, the final piece of the puzzle needed to spur net-zero-aligned industrial production in the EU.

There are still questions on implementation even at this late stage, but the EU is the one market that is pulling all of the relevant policy levers. The bar for success is high: CBAM needs to successfully reduce emissions in Europe without sacrificing its industrial competitiveness, while also encouraging other jurisdictions to implement stringent emissions policies. We will soon know if it works or not.

Elsewhere, China is expanding the scope of its carbon market and planning to introduce absolute emissions caps. It is also ramping up efforts on hydrogen with new policies to fund the scale-up of hydrogen production. Japan’s GX-ETS carbon market will launch in 2026 too, which could lay the foundations for the country’s industrial sector to decarbonize. While policy change has slowed investment in the US, the country will still be the largest host for carbon capture projects until the end of the decade.

In the meantime, there will be gradual progress on emerging technologies. We now expect global carbon capture capacity to increase more than fourfold by 2030, to exceed 200 million metric tons per annum. Clean hydrogen production rises to 5Mtpa by the same year. While this is a much lower figure than previously expected, it still represents a sixfold jump over the next five years. As for sustainable aviation fuels, we project a 10-fold increase from 2024 to 2030, reaching 3.8% of global jet fuel demand by the end of the decade.

The numbers remain small and expectations are much lower than before, but progress is still being made.

Winning and losing in the climate race

We are in a fragmented, multi-speed transition. Progress will continue, but different regions are placing different levels of priority on clean energy development, and different technologies are scaling at different speeds. And as I’ve hinted in this article, we are starting to see relative winners and losers in the clean energy race.

But take a step back and remember that the physical impacts of climate change wait for no one. Our colleagues in Bloomberg Intelligence have calculated that the world suffered $1.4 trillion of climate damages in 2024 – a figure that is currently doubling with each decade — and data limitations mean this is likely to be a considerable under-estimation of the true costs.

In 2025, we saw devastating storms and floods in Southeast Asia, deadly heatwaves in Europe, extreme storms and tornados across the US – and who can forget the wildfires in Los Angeles at the beginning of the year? Climate damage is already harming communities and economies around the world, and it is only going to get worse.

In a world where the energy transition fails, we will all be losers – but that is not the world we’re in. True, we can now see that global warming will not be kept below 1.5 degrees Celsius, and in my view we should not be surprised. The extremely sharp emissions reductions required to achieve this goal were always going to be monumentally challenging to deliver.

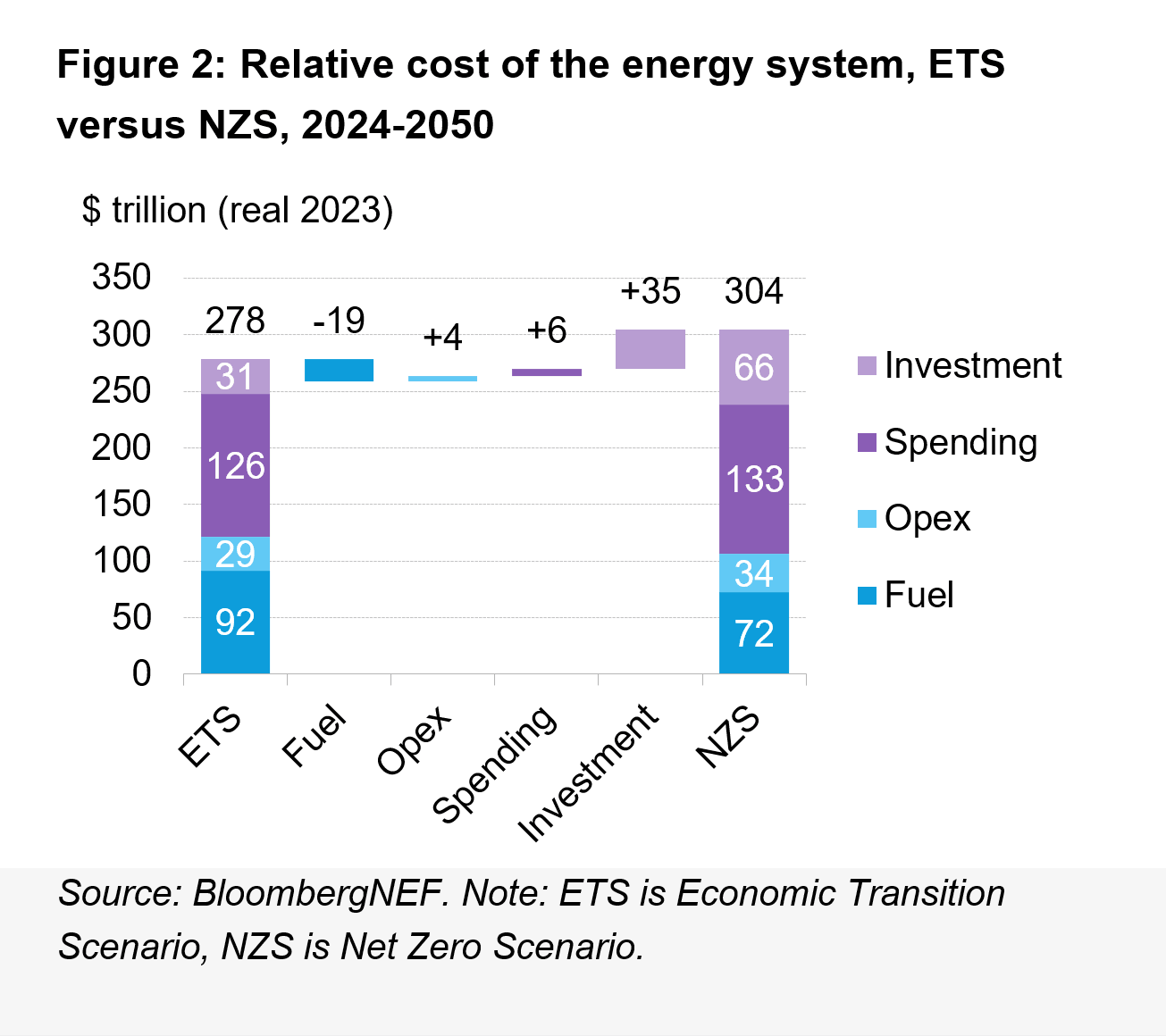

But the clean energy transition still holds the keys to a better outcome. In our New Energy Outlook last year, we presented a new Economic Transition Scenario showing that a global peak in emissions could occur immediately if we only deployed clean energy technologies in line with a cost-effective base-case trajectory. We also demonstrated that a faster, net zero-aligned transition carries only a 9% higher cost for the energy system to 2050, compared with the base case. The payback, in reduced climate damage, improved air quality and human wellbeing, should speak for itself.

This spring, BloombergNEF will publish a new climate scenario that provides a pathway to keep global warming well below two degrees, in line with the headline goal of the Paris Agreement. This will not be a top-down narrative scenario, but a bottom-up analysis of technologies, sectors, countries and economies, showing a credible pathway to a climate-safe outcome. At a moment when countries face competing priorities, we should remember that the energy transition will keep progressing, and a pathway to stabilizing the climate still exists.