By Tai Liu, Oil Specialist, BloombergNEF

A revival of Venezuela’s oil sector could materially reshape global oil markets over the long term, given the country’s roughly 300 billion barrels of proven reserves — the largest in the world, according to OPEC. But those reserves come with major constraints.

Most Venezuelan crude is high-sulfur and heavy, making it costly and technically challenging to transport and refine compared with light, sweet grades. Years of mismanagement and chronic underinvestment have further hollowed out the industry.

Any meaningful recovery would require time, large-scale infrastructure rebuilding, and billions of dollars in capital — along with sustained involvement from international oil companies. Securing that level of commitment remains a tall order as oil majors prioritize more competitive, lower-risk projects elsewhere.

Discounted oil

The majority of Venezuela’s 300 billion barrels of proven oil reserves are located in the Orinoco Oil Belt. The region produces crude oil that is heavier and more sulfur-intensive compared to international crude grade benchmarks such as the US’s West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Europe’s Brent crude. Orinoco crude has an American Petroleum Institute gravity – or API gravity, which measures petroleum density – of 9.5–12, and sulfur content of 4%–5%, making it comparable to Canada’s oil sands bitumen.

These grades often need to be blended with diluent (such as condensate or naphtha) to make them easier to transport and process. Furthermore, refining such crude also requires specialized refining equipment, like cokers. As a result, these types of heavy, sour crude trade at a material discount compared to international benchmarks.

Based on recent prices for different crude grades and solving for specific gravity, BloombergNEF estimates Venezuela’s heavy crude (that is, without blending) should trade at roughly a $7- to $10-a-barrel discount compared to WTI.

Safer alternative options to invest

On the investment side, President Donald Trump has said US oil companies will invest billions to rebuild Venezuela’s oil industry. However, it is unclear how much capital US oil majors are willing to commit, or how quickly. One estimate suggests an annual capital commitment of $10 billion over the next decade.

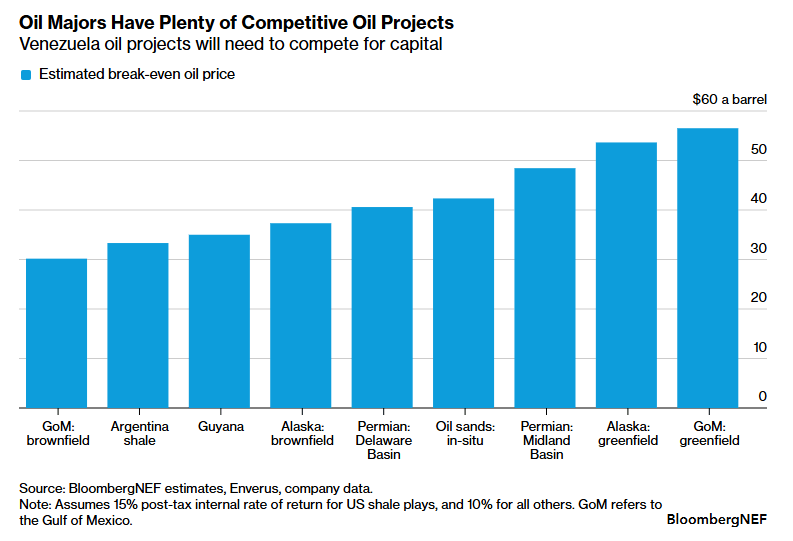

From an investment perspective, Venezuelan projects will need to compete for capital, and US oil majors have plenty of options. Exxon Mobil holds major acreage positions in Guyana and the Permian Basin. BNEF estimates Guyana projects can break even near $35 a barrel, and the Exxon-favored Permian Midland Basin has an average break-even oil price of $48 a barrel. Exxon’s breakeven in the Midland Basin is likely lower, as the company is deploying a new type of proppant that improves well recoveries.

Chevron faces similar choices. The company has investments in Guyana’s offshore Stabroek Block, through its acquisition of Hess Corp. Chevron is also active in the Permian’s Delaware Basin, where break-even prices range from $37 to $44 a barrel. The company also has major positions in the Gulf of Mexico, where brownfield projects are very competitive and can break even at oil prices as low as $30 per barrel. Greenfield projects break even at a considerably higher level of $56.50 per barrel.

ConocoPhillips is a major player in Alaska and Canada’s oil sands, among others. Greenfield projects in Alaska have an estimated break-even oil price of near $54 a barrel, while brownfield projects are economic at $37 a barrel. Meanwhile, the company’s Canadian in-situ oil sands projects require about $42 a barrel to break even.

Venezuela’s oil production had an estimated break—even price between $42 and $56 a barrel in 2020, according to Rystad Energy, with the Orinoco region at $49.26 a barrel. While this is lower than greenfield projects in the Gulf of Mexico and Alaska, it is considerably higher than many of the other projects and acreage within these oil majors’ portfolios. With abundant lower-cost projects in stable, predictable political environments, US oil majors may be reluctant to commit substantial capital in Venezuela without stronger incentives.

Planning for the long term

In short, restoring Venezuela’s oil industry would require companies to overcome several hurdles: crude output that trades at a considerable discount to global benchmarks, billions of dollars in capital commitment, and intense competition for capital within global portfolios.

Even so, with some oil fields declining by roughly 15% a year and demand expected to remain elevated for decades, long-cycle investments in Venezuela could still make commercial sense over the long term. Just as national oil companies such as Saudi Arabian Oil Co. and Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. have historically benefited from asset longevity, US oil majors may yet find a path to similar long-life returns, if the risks can be managed.