by Nilushi Karunaratne, Senior Editor, BloombergNEF

It’s yet to be determined if climate change has played a direct role in the latest wildfires raging across Canada and the haze still lingering in North America. But global warming is exacerbating the extreme conditions like drought and heatwaves that help fuel such infernos.

With California’s fire season due to get underway, a study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences concludes that the increase in forest area burned in the state over the past 50 years is almost entirely due to human-caused climate change. The scorched territory could expand by more than 50% in the coming decades, adding to the growing list of warnings about the need to drastically curtail our greenhouse gas emissions.

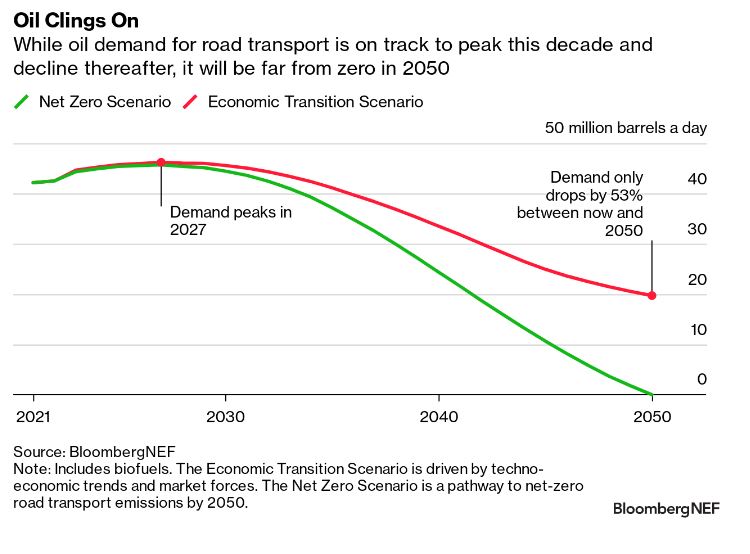

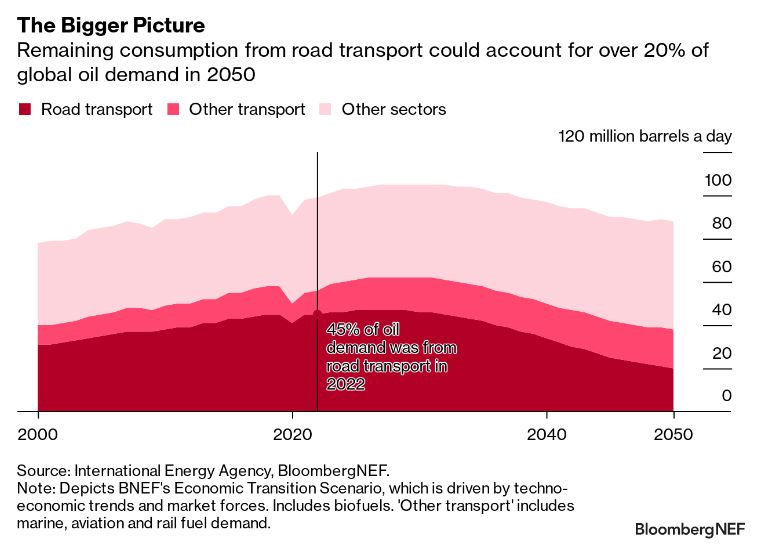

It’s good news then, that the world’s demand for oil is set to peak this decade. As more people switch from gasoline and diesel guzzlers to electric vehicles, oil consumption for road transport is on track to crest in 2027, according to a report from BloombergNEF.

But while the ceiling will be reached, the thirst for oil won’t be disappearing anytime soon. Based on the current trajectory, the amount of oil needed to power cars, vans and trucks will roughly halve between now and 2050, leaving close to 20 million barrels a day of demand in play. That’s about as much oil produced by the US last year (when counting crude, all other petroleum liquids and biofuels).

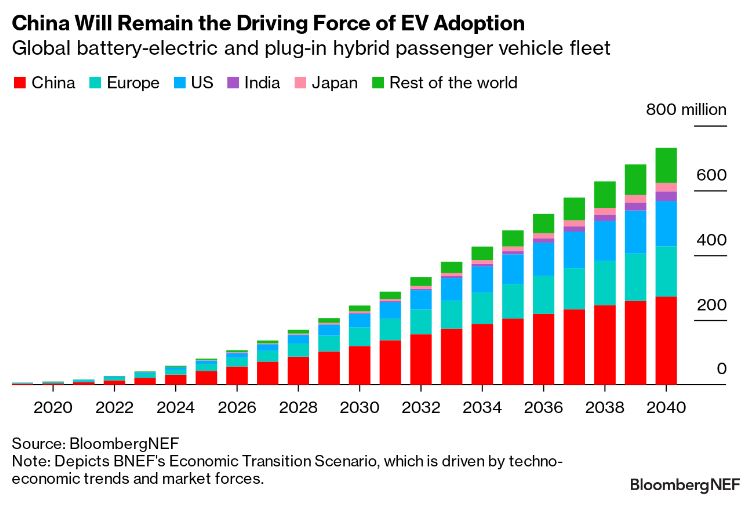

The headway made to date and the progress to come shouldn’t be understated. There were 27 million battery-electric and plug-in hybrid passenger vehicles on the world’s roads at the end of last year and that’s expected to jump to 41 million in 2023.

The growth will be driven by leading market China, where local incentives and restrictions on internal combustion engine vehicles are outweighing the phase-out of national subsidies, as well as the US, where sales are being buoyed by the EV tax credits included in the Inflation Reduction Act. Europe’s momentum will also continue this year, albeit at a slower pace than previously projected as the region is squeezed by supply chain issues, a cost-of-living crisis and weaker pressure from fuel economy targets.

It’s almost certain that we’re heading for an electric age of transport. Nonetheless, the current fleet of zero-emission cars is saving less than 300,000 barrels of oil a day – a drop in the ocean compared with the more than 24 million barrels a day of fuel being burned by the 1.2 billion internal combustion engine vehicles in circulation.

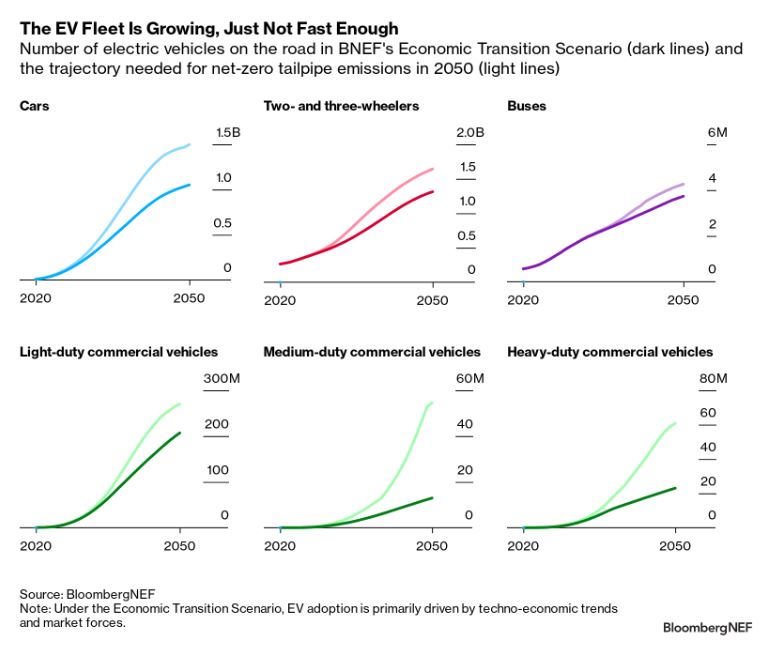

Looking ahead, as climate goals push policymakers to clean up transport and the long-term decline in battery costs makes EVs cheaper, more drivers are set to make the switch. BNEF’s Economic Transition Scenario, which is based on techno-economic trends and market forces, sees over 1 billion passenger EVs whizzing around in 2050. But that’s still 445 million short of what’s estimated to be needed to completely ditch oil and reach net-zero road transport emissions.

While the Economic Transition Scenario does envisage some major markets, such as China, Germany and the UK, coming close to 100% of passenger car sales being electric by mid-century, this is far later than is required and other countries are even further off track.

It’s not just a passenger car problem, with all vehicle segments on course to lag a net-zero trajectory over the coming decades. Putting this conundrum in dollar terms, getting to net zero is the difference between an EV market that reaches $88 trillion of sales between now and 2050, versus one that only gets to $57 trillion.

Decarbonization of vans and trucks has been slow off the mark and the penetration of alternative drivetrains in long-haul, heavy-duty transport in particular is set to prove more challenging. Scaling up greener commercial vehicles for delivering goods is a less sexy topic than the battle to dominate everyday consumer cars – the competition between Volvo AB, Daimler Truck AG and Traton SE hardly ignites the same excitement as the horse race between Tesla Inc., Ford Motor Co. and General Motors Co. But zero-emission vans and trucks are just as important for averting climate disaster as cars.

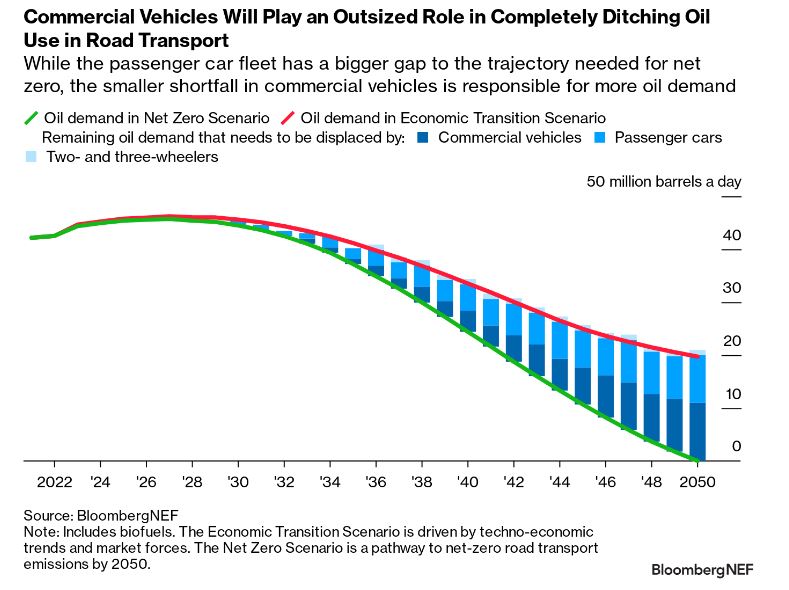

Of the 20 million barrels a day of oil demand left over in 2050 under BNEF’s Economic Transition Scenario, around 9 million barrels a day is from the 445 million gasoline and diesel passenger cars due to be around at that time. Yet that is exceeded by the 11 million barrels a day of oil consumed by 142 million commercial vehicles running on an internal combustion engine – a much smaller but more fuel-intensive fleet.

The reason why any of this matters is because road transport is the largest component of global oil demand, accounting for 45% of the total last year. EVs may not completely erode demand for oil, but they will make a considerable dent in the long term. However, the decline in consumption won’t necessarily translate to a collapse in oil prices. If investment in new supply shrinks at a faster rate than demand, prices could remain elevated and volatile.

Road transport is a sector that already has relatively cost competitive alternatives to fossil fuels available at scale today, unlike industries like aviation and shipping where the options remain limited by technological and economic barriers. That means there’s scope to expedite the arrival of peak oil demand and get on track for zero consumption for road transport by 2050, although this will depend on many players stepping up – governments, investors, automakers, battery manufacturers, charging operators and miners, among others.

There are a lot more policy tools governments can use to boost EV adoption – from tightening fuel economy standards and legislating phase-out dates for internal combustion engines no later than 2035, to additional consumer subsidies for EVs and support for battery innovations and charging infrastructure. They also need to facilitate the buildout of renewable energy capacity. After all, an EV is only as green as the grid it charges from.

Easing grid connection delays and permitting obstacles will be essential to ensure the adequate rollout of chargers. Not only will a dense public charging network increase consumer confidence in adopting EVs, it will also make them more comfortable with lower ranges for vehicles, reducing the pressure on raw material supply chains for batteries.

Meeting lithium demand for batteries, for example – which BNEF estimates will reach 10 million metric tons lithium carbonate equivalent by 2050, a 22-fold increase from today – will be challenging in the absence of new chemistries that lean on other metals, recycling and investment in new reserves.