Colin McKerracher

Head of Advanced Transport

BloombergNEF

Electric vehicles should be cheaper to buy on average than combustion vehicles in about five years, without subsidies. That’s the main conclusion from new analysis from BNEF, but the high-level summary hides a lot of nuance, and I want to highlight some of that here.

First, a note on what EV ‘price parity’ is and isn’t: “price parity” refers to the point at which an automaker can theoretically build and sell an EV with the same margin as a comparable combustion vehicle, assuming no subsidies are available.

In practice, actual vehicle pricing strategies will vary by automaker. Just last month Ford announced that its electric F-150 Lightning would start at a similar price in the U.S. to the traditional F-150, even though the manufacturing cost is likely still higher. There are also a lot of government policies and subsidies affecting the market right now. In markets like Norway for example, EVs are already cheaper up front because of favorable taxation.

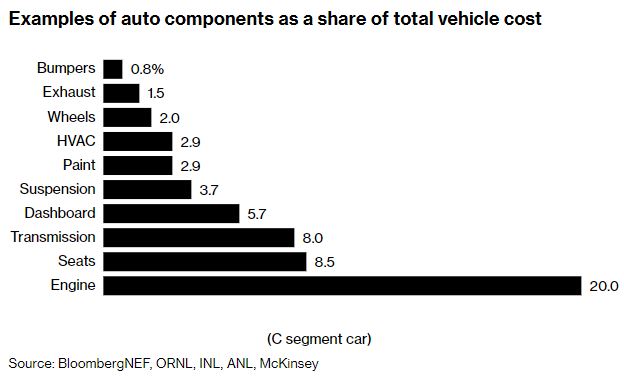

For its analysis, BNEF looked at all of the different components that go into a vehicle and evaluated those that would be affected by a shift to EVs; it also measured how those costs would change over time. There are the obvious parts, like the drivetrain, but there are also less obvious ones like wiring (which can be cheaper in an EV) and the heating and ventilation system (likely more expensive on the EV because of the lack of thermal output from the engine).

One of the most interesting results of the analysis was that battery pack prices need to drop well below $100 per kilowatt hour (kWh) for EVs to reach parity — that rate has long been held out as the benchmark for reaching this point. But given consumer preferences for higher ranges and heavier vehicles the magic number looks closer to $80/kWh in Europe and the U.S., and even lower in some other markets with cheaper vehicles. Taking it a step further, $60/kWh is a good benchmark for when EVs are cheaper than combustion vehicles in all segments and countries. BNEF expects battery prices to reach $80/kWh in 2026 and $60/kWh in 2029, down from $137/kWh in 2020.

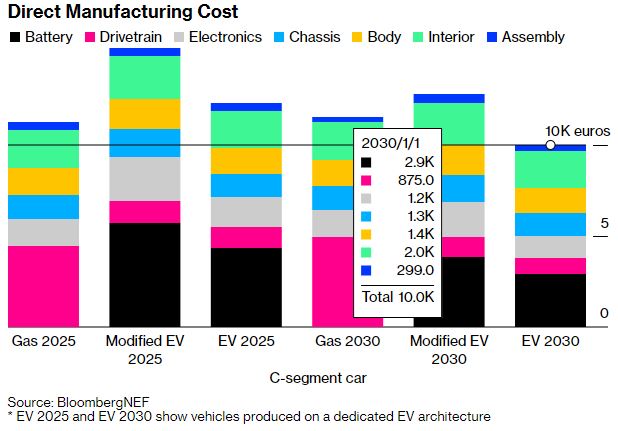

Another interesting finding is how important it is for automakers to switch to dedicated EV architectures for their upcoming models. Many of the EVs available today are still based on modified, or multi-energy platforms, where the automaker has repurposed an existing platform to be able to support electric variants. This approach provides advantages in terms of being able to respond quickly to changes in demand between traditional combustion engines, plug-in hybrids and pure EVs, and being able to benefit from the economies of scale across those. But it has all sorts of compromises that add costs and make manufacturing more complex. EVs built on these multi-energy platforms, BNEF’s analysis shows, never really reach parity.

The analysis also flexed several sensitivities, including increasing the required driving range by 50%, using higher battery material prices, changing vehicle efficiency assumptions, and other factors. Even pushing these up, EVs still reach price parity in almost all combinations by 2028 in the most pessimistic case, and by 2025 in the most optimistic scenario. That’s now just one product cycle away, and some automakers will get there sooner than others.

This doesn’t mean EV adoption will go to 100% right after hitting price parity. The analysis used average vehicle prices, but each vehicle segment has a wide range of different models within it, some of which are priced well below the average. In the smaller vehicle segments, stripped down, low-performance, low-cost internal combustion vehicles could be hard to beat on price for some time.

In Europe, that may become a moot point, since regulations will probably make it unattractive for automakers to sell anything other than plug-ins by 2030. But in other regions of the world, particularly emerging economies where capacity to grant subsidies is limited, price parity is still an important point to watch for EV adoption.

The full report was commissioned by Transport & Environment and can be found here. BNEF’s long-term Electric Vehicle Outlook, out now, looks at this topic more and what it means for global EV adoption.