By Maggie Kuang

Head of APAC LNG

Bloomberg New Energy Finance

The shale revolution is leading the world to a future of abundant and affordable oil and gas. The technology of liquefying natural gas (LNG) is increasingly used to ship gas produced in cost-competitive regions to where gas demand is growing but where local gas production is falling. Structural reforms in the power and gas sectors and rising competition from renewables and alternative fuels are reshaping the global LNG industry. In this article, Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) elaborates on the implications and describes the future of LNG.

Diverse drivers to LNG demand

Traditionally, LNG has been used largely for power generation. However, this is changing as market conditions in traditional LNG-importing countries change and new importers with different dynamics join the market. BNEF expects:

- The growth in demand for LNG used for baseload power generation will be limited as gas in many major economies can’t compete with renewables.

- Rising renewable penetration will expand LNG’s role in providing flexible power generation to balance the electricity grid in many major economies.

- The use of LNG in the industrial and transport sectors will push up gas demand, particularly in Asia where environmental concerns are on the rise.

- The opportunity for LNG in baseload power will be mostly in floating storage and regasification-based emerging markets that are plagued by power shortages.

Demand shift from JKT to other Asian countries

Asia will continue to lead the growth in demand for LNG, with BNEF forecasting the region will maintain its 70% market share in the coming decade. However, demand growth is shifting from the traditional Asian markets of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan — often referred to as JKT — to ‘emerging Asia’ led by China, India, South and Southeast Asia.

JKT’s share of global LNG trade is likely to fall from today’s 49% to 25% in 2030. In Japan, nuclear restarts are driving down gas power generation which is fueled by imported LNG. In South Korea, LNG demand is likely to be flat as new coal and nuclear power, which is cheaper than gas power, is scheduled to come online in coming years. In addition, the growth of renewables is becoming a threat to gas in the longer term. With strong policy support, a jump in LNG demand is difficult to see. Taiwan’s LNG demand growth will be largely constrained by its LNG-receiving capacity.

In contrast, ‘emerging Asia’ will become the engine driving the growth in demand for LNG. The share of combined LNG demand from these countries globally will rise from today’s 23% to 42% in 2030. Improving macroeconomics, stricter implementation of environmental policies and ongoing gas market reforms will continue to push up China’s gas consumption and LNG imports. India’s LNG demand is expected to be largely driven by industrial sectors where fuel-switching opportunities exist for LNG as a feedstock. In South and Southeast Asia, LNG demand will be primarily driven by power demand growth and a reduction in local gas production.

Global LNG demand/supply-capacity balance

How big is the demand growth?

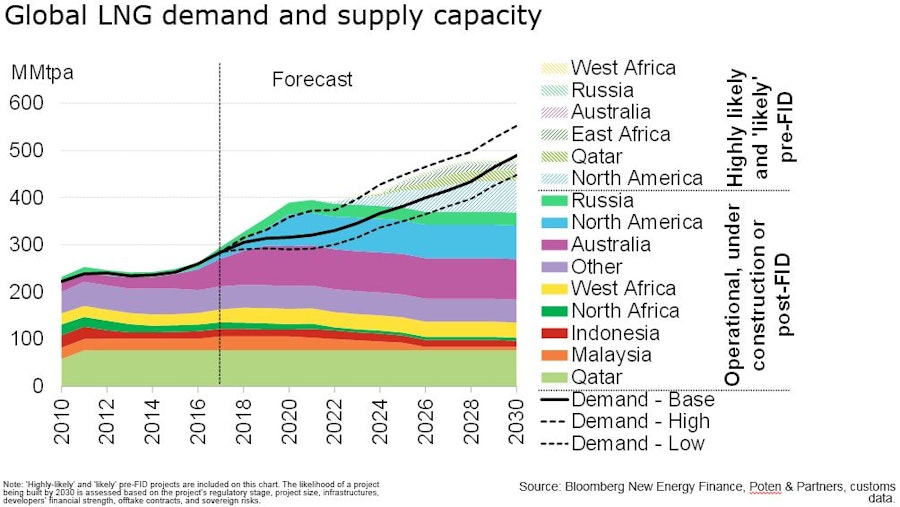

The world consumed 285MMt of LNG in 2017. The substantial expansion of global LNG trade in 2017 is unlikely to repeat in 2018 and further slowdown is expected in 2019-22. Global LNG demand is expected to reach 330MMtpa by 2022. Post 2022, a significant decline in domestic production in Southeast Asia and Europe will drive a rebound in global LNG demand growth. By 2030, BNEF expects to see global LNG demand reaching 490MMtpa.

Demand could accelerate quickly in various markets, though. Upside potential in demand growth of 40-65MMtpa exists across different countries in the world, including China, South Korea, Japan, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Europe and Kuwait.

For China, policy strength and economic growth are the wild cards, while the biggest uncertainty in Japan is nuclear restarts. For South Asia, the price of LNG and progress toward expanding infrastructure are the major contributors to a swing in demand. For Europe, LNG prices and geopolitics will be the key triggers.

“Lowering LNG prices during the early 2020s and accelerating infrastructure build-out in South Asia are the key to unlocking LNG demand in the region,” BNEF analyst Maggie Kuang said. “The market needs to take action now to grab the opportunity then.”

Evolving LNG purchase models

Traditionally, LNG importers buy LNG via long-term, take-or-pay, and delivery location-fixed contracts. As LNG demand becomes less certain due to competition from renewables, alternative fuels and market liberalization, LNG buyers are in need of flexible LNG contracts more than ever. Such contracts would allow buyers to reduce volumes, cut tenures, and request different delivery locations when needed. However, negotiations between buyers and sellers haven’t been easy.

BNEF data shows that the signing of new LNG term contracts has been declining every year since 2014. Only 20MMtpa of new contracts were signed in 2017, 10MMtpa lower than the previous year. Of the 20MMtpa signed volumes, only 1MMtpa had tenure shorter than 5 years. Short-term contracts were able to be sold only by portfolio players, trading houses, and suppliers with old projects whose marginal cost of supply is low.

Requests for flexible volumes and tenures pose significant challenges in terms of project finance for new supply projects. The nature of traditional project financing does not accept high uncertainties on project cash flows resulting from flexible contracts. Portfolio players and trading houses will need to participate in financing or offtaking future supply projects given their expertise on optimizing assets and hedging risks.

Traditionally, contracted LNG prices are mostly linked to oil prices, though LNG buyers have shown a strong desire to delink from oil prices in case of a spike in the future. However, such voices have faded at times of lower oil prices and there has been no consensus from buyers on the most suitable indexation option in LNG contracts. Depending on where oil and gas hub prices are, LNG buyers are expected to switch between the two from time to time.

Buyers have been making efforts to establish Asia gas hubs. The argument is that regional gas hubs are needed to create a gas-on-gas indexation that reflects local demand and supply. Such Asian indexes are then expected to find increasing relevance as benchmarks/reference points in long-term LNG contracts.

Japan, China, and India have all seen some progress in setting up the required trading platforms. To discover the right price point, these planned hubs will need sufficient number of market players and volumes of transactions of gas and/or LNG. From market players’ perspective, free competition between pipeline gas, LNG, indigenous production, and substitutes fuels will best reflect gas fundamentals and help discover the fair price for LNG. However, it would be hard to see full competition among these fuels without a liquid and liberalized gas market, connected by extensive pipelines serving a sufficiently large gas demand.

A supply shortage risk and price spike ahead?

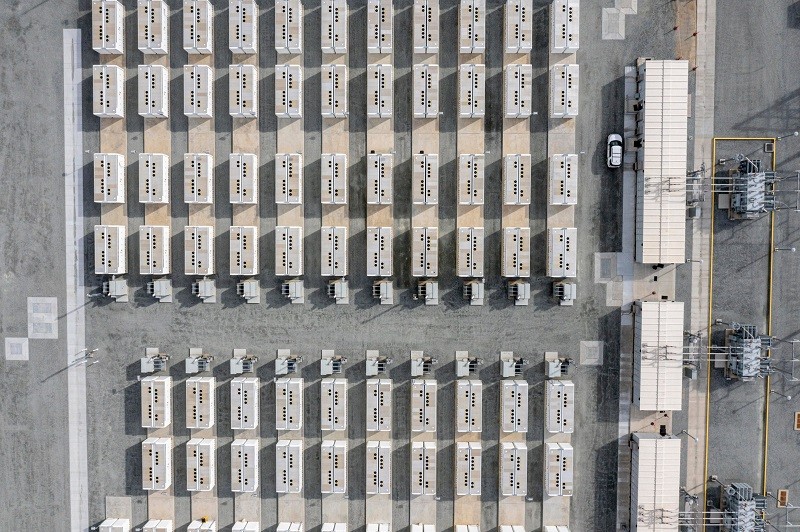

BNEF anticipates about 30-33MMtpa of new capacity will be added from 2018-20. Australia has the last batch of projects to come on-stream before the end of 2018 but full ramp-up will take a couple of years. The boom in U.S. LNG supply will end in 2020. Global capacity will peak at 396MMtpa in 2021 and will begin to fall behind demand post 2025. To support further demand growth, final investment decisions (FID) on new supply projects will need to be made in the next few years to provide sufficient supply post 2025.

Given an average 5-year lead time in LNG project development and construction, 2018-20 is a crucial window in which to reach final investment decisions. The earlier a project takes an FID, the better it is positioned to price its supplies/volumes. “However, many projects are facing financing hurdles at the moment as buyers want flexible contracts — which is not going to help these projects secure financing,” BNEF’s Kuang said. Bundling multiple short-term contracts to cover 10-20 years on a single project is being tested out with some banks’ project finance teams. “The risk of running into supply shortages might be just a small possibility, but we are also unlikely to see a sudden wave of new projects taking FID,” Kuang added. As a result, prices could rise in the long term, but BNEF is skeptical that a trend will emerge in which prices skyrocket.

BNEF considers that there is roughly 362MMtpa of pre-FID capacity with any chance of coming online by 2030. Of that capacity, about 118MMtpa is likely to achieve FIDs over the next 5 years based on BNEF’s assessment. Half will be located in the U.S., while others will likely come from Qatar, Mozambique, and Papua New Guinea. BNEF’s analysis of the likelihood that a project will be built by 2030 is based on factors such as how far it has advanced with regulators, size, infrastructure, a developer’s financial strength, the existence of offtake contracts and sovereign risks.

For more detail about BNEF’s coverage and analysis of LNG markets, read a public excerpt of our Global LNG Outlook.

This article was originally published on the KNect365 website and is republished here with permission. You can read the original article here. BNEF’s Head of EMEA, Seb Henbest, will discuss this and other energy-related topics at the Flame conference on May 16 in Amsterdam. You can find out more about the agenda here.